| Brestward Ho - Main Page |

|

|

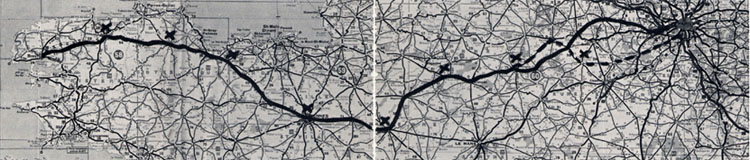

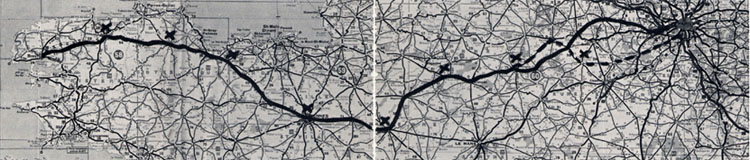

Ten minutes later "Oppy" dropped the flag and we were away at exactly 1600 hours on Monday 6th September. From a clear sky the sun was coming down hot on our faces, with a moderate wind on our backs. In no time I had run out of gears in an upward direction and was on the 50 x 16. Already groups had formed, and in the distance on the rise I could see a leading packet which doubtless contained Richard and De Munck with their 53 x 13s in action. Our good "D" road crossed main highways, leapt over dived under autoroutes. After 10 miles we were on N12, the Great West Road of France which links Paris with Brest, and that was the way "Oppy" travelled in 1931. In 1971 however, heavy traffic so near Paris would not digest a giant cycling club-run with 330 members, and no sooner were we on N12 than we were off it and pedalling along D11 in a north-westerly direction towards Septeuil. This is a pleasant rolling road which I have used several times when riding on my own from Paris of Rouen. Now I had plenty of company. Despite my good intention of taking things easily for the opening miles, I couldn't resist having a go in the general tear-up and even stepped forwards a group or two. Then up from behind came Barry Parslow, his well-clothed Herne Hill contrasting with my mini-skirted lady-love Lejeune. "Look at the madmen" Barry exclaimed "Don't take any notice of them. They were just the same last time. You'll see a lot of those fellows clapped out at the Controls and by the roadside coming back. Let them get on with it." The advice, however, was given in the spirit of "Don't do as I do, but do as I tell you". After riding with me for a few miles Barry suddenly sprinted away, saddle-bag swaying, a dauntless Duke of Marlboro out to smash a platoon of French who had just crept up on us from the rear. For my part, although I was impulsive when the road was going down, or "along", or rising slightly, I was cautious when it tilted upwards to any marked degree. Like most veterans, I know that the surest way to bring on leg and lung trouble is to try to follow wheels uphill that are just that little bit too fast for your liking. During the week-end I had studied this part of the course on a cut out section of a large-scale Michelin map which I now had tucked in a jersey pocket. There was no need to consult it. As well as the police on major corners there were plenty of village spectators directing us on to the right road with shouts of encouragement and advice. Considering the enormous field, it was quite remarkable after two hours' riding to find myself entirely alone on the road, yet with 200 or so riders not far behind. On the outskirts of Nonacourt the route hit N12 again, but it was too early yet to embrace it Brestwards. It was straight over towards Brezolles. I stopped in the village to buy some grapes and bananas, and was riding slowly eating them when up came a group of 20 pedalling steadily at about 17 m.p.h. They all had well-filled bags on the 'bars, two or three spare tyres on back carriers and hefty electric torches attached or lashed on the 'bars or front forks. I slipped in with them and chatted to my triple-chain-wheeled neighbour. I learned that they were a group of cyclos from various clubs in the Parisian area, not out to "make a performance" but to keep together if they could and finish in about 70-75 hours. I was in the right company at last. The road was flat, the wind still kind, the sun now low and crimson in the west. Rising out of the saddle of a distant hill, the moon started her pursuit from the opposite side of the celestial track. Then from that dreamy contemplation of the heavens I came back to earth with a thud. The front tyre was flat. I had already given a hopeful pump during the stop at the greengrocers, I would have to fix it properly while the light lasted. Of the two spare tyres, I selected the used Clement Criterium rather than the new and heavier Wolber. Better to have the light one on the front and keep the Wolber in case it was needed for the back. Besides I have a bad record of wrestling with new tubular tyres which always seem to have been made an inch too small for my rims. The Clement slipped on easily. While I was inflating a bent old chap waddled to his own garden pump and filling my bidon with cool water. "The others are miles ahead!" he said encouragingly. "Maybe--but there are about 200 still behind!" I replied. "Voila--un peloton!" cried my water-carrier. There was, too, about the same sized bunch as the one in which I had recently been so happy, but not moving with quite the zip. I joined in and again sounded out the ambitions of those present. Three of those I spoke to were on P-B-P for the first time, a bit nervous of their ability to last. At the front were two members of their club, experienced Bresters who had 80 hours as their target. In shorts, jerseys, ankle socks and little caps only one thing stopped some of the bunch from looking like real racing men. They had hairy legs! I noticed, too, amid the Campag., Stronglight and T.A. alloy chain-sets several using good old-fashioned steel cranks and cotter-pins. As well as 20 cyclists in my new group there was also a motor-cyclist gendarme. He cruised about 100 yards ahead waving down oncoming traffic, occasionally stopping at a cross-roads to see us safely across and then roaring cheerfully by to resume his role of pathfinder. By now the sun had been eliminated from the heavenly pursuit and the silver-medal moon rode slowly over on her own. We didn't really need lights yet, but at a friendly signal from the gendarme, switched on in our various ways. Some flicked a small lever under the seat cluster to set the dynamo humming. Others had small front and rear lamps powered by batteries carried in cases fixed to various parts of the bicycle. The majority had big torches on the front and a scratch assortment of lamps behind. My own front Pifco brought murmurs of approval, and when the rear Ever-Ready was switched on and shone like a beacon in the gathering night, I had quite an At Home receiving visits from interested companions. One fellow thought I was the inventor of the lamp, was trying it out in Paris-Brest-Paris and would put it out on the world market and make a fortune. He was surprised to find it was compulsory in Britain to use a rear lamp of such efficiency and that there were millions in use. I was the odd man out in other ways too. Apart from two capes and two tyres on the back carrier and a bidon in the down-tube cage, I had no other luggage. My companions were well laden. Their front bags bulged. One or two had small bags attached to the rear carriers with those useful hooked elastic strands which the French call San-duffs, this being their pronunciation of Sandow (the strong-man) who used to train with expanders. All had at least two bidons, some three, in cages on the seat and down-tubes. During my early campaign in the fighting line, Barry Parslow's wired-on tyres were conspicuous among the lightweight tubulars. Now I notice that several of my neighbours also had spare inner tubes in their luggage. I was among the transistor carriers, too. One fellow had his in a front jersey pocket and switched on the nine o'clock news, then over to a programme of light music and song. So now it was a black and white minstrel show. White under the moonlight, black where the wandering road plunged through the woods. Through those gloomy patches the police BMW scattered its kindly light, the pilot swerving to the left from time to time to bring on coming traffic to a halt. This big-time race treatment was good for the morale of our bunch of small-time international cycle sportsmen. I suppose by now, though, some motorists were getting a bit fed up. They may already have had to pull up for a dozen such groups as ours, and there were as many more still behind. Most drivers obeyed police orders. One speedster drove on with our gendarme bravely riding straight at him, only swerving away in the nick of time. Another fraction of a second and our escort would have become a guardian Angel. At Logny we picked up a party of a dozen, one of whom had punctured, and now had only 10 miles to go before the first control at Mortagne. There were more than 30 of us together, too many for the liking of some experienced cyclos who knew what a crush there would be round the official table if we all arrived together. So up went the pace as the "selection" began. As in all branches of my Paris-Brest-Paris I opted for the happy medium. I kept with the first 15 until three miles from home when the climbers went away, and I rode into Mortagne on my own. The first street lights revealed banners welcoming the Valiant Riders of Paris-Brest-Paris, and the main square was packed with official and helpers' cars. On the far side twin café-restaurants had a Control banner wafting in the breeze over the doors, and some 50 bikes were stacked along the walls. "Monsieur Wadley--here we are!" It was Monsieur Chambon, and the U.S. Creteil van with all my stuff laid out neatly at the back. They advised me to get in quickly and have my Route Card stamped while the table was clear. I told them of my puncture. At the cafe door I literally bumped into Barry Parslow who was about to get onto the road after a short stop. He had been in trouble. A puncture in one of those wired tyres, and then a crash when riding with a bunch. There was a nasty cut on his arm and bruises on the way. The Control table was on the right on entering one of the cafes which was bursting with activity, 30 riders eating or impatiently calling out across to the sweating staff. They were just as busy next door. "No 339" said the time-keeper "Arrived at 22 hours10 minutes." The figure was entered by one colleague into my Route Card and by another on the master check. Outside my friends had a bowl of soup ready. The punctured tyre had been removed from the back carrier and replaced with a new one. The bidon now contained hot tea. This was marvellous treatment, but I now realized even before the start at Paris that I was not worthy of it. I knew that waiting around for me at each Control my friends would fall so far behind that they would be unable to get on to the next to look after the younger members of the expedition. Those boys had, in fact, arrived at Mortagne 50 minutes before me and had been off after a 15-minute stop. I planned to be around Mortagne a little longer than that. I had smelled steak in the restaurant. . . I told M. Chambon to forget about me, to get on up the road and look after Youth. Old age would take care of itself. I took the front bag from the van, filled it with essentials and strapped it to the 'bars. As I expected, the Pifco lamp which had been perched quite satisfactorily on its clip until now, protested at the arrival of the bag and had to be held in its place by a small Sanduff band. I bid my friends au revoir, and they quickly picking their way through the cars to get on to the next Control. I followed my nose towards the steaks. Some hopes. The staff had been hard at it now for a couple of hours, and had not yet found their second wind. I heard an impatient customer with a Lyon accent complaining he had been there for a quarter of an hour and was still waiting for his first dish. Then on to the scene came the T.V. crew whose vehicles I had seen parked outside. With them was a Tour de France colleague Daniel Pautrat who was doing the commentary for the French national programme. In no time Daniel had the garcon organised and at last the Lyon's dentures were busy on grated carrots and so were mine. A steak followed with green beans, cheese, fruit and a big bottle of Vittel water. For the first time in 20 years I had an evening meal in a French restaurant without wine. In this respect there was to be no happy medium. No wine on this trip, and no beer. Wine makes you drowsier than ever on sleepless nights, and one beer during a hot day leads to too many others. While I ate, Daniel Pautrat told me that a leading group of 24 had arrived at 20-45 having covered the 92 miles in 4h 45m. After being "Controlled" they were off again within three minutes. I paid up--I forgot the price, but it was much cheaper than expected, as indeed was the case at all Controls--and slipped into the track suit. Having been at the Control for more than half an hour I had to have my Route Card stamped again with the time of departure, and began the second short stage on my own, the wind still fresh behind, the beaming moon high and clear. Mortagne had marked the end of the of the police escort. We were now on N12 for a 63 mile stretch, although it would not be ours for keeps until Rennes. So easy was the

going that I decided to save batteries by using the dynamo. The

switch-over only By battery light, then, I kept within French law on the bright broad and easy road to Pré-en-Pail. While Paris-Brest-Paris cyclists make the journey once every five years, it is a once or twice-a-week job for big truck drivers. Those heading west gave us a wide berth on passing, those approaching dimmed lights well before the point of dazzle at which most motorists start thinking about it. Most drivers gave a friendly toot of the horn, many mates leaned from the cabins with a word of encouragement. The French dictionary has the same word for us both, routiers, or roadmen. The kilometres-stones passed rapidly by. Without trying I bagged 30 of them (18 ½ miles) in the hour and could imagine the leaders with their huge gears in action collecting half as many again. In no time I was through well-lit Alencon and following the N12 signs to Pré-en-Pail, the second Control and only 31 miles from the first. Why another stop so early? I don't know how these Control towns are fixed, but in this case it may be because of the excellent facilities provided at the Hotel Normandie, afterwards voted the most efficiently run of all the compulsory halts. At rush-hour no doubt the service would not be so good, but when I arrived on my own it was excellent. The Route Card stamped, I went into the little back restaurant one side of which had been turned into a cyclists' supermarket. Two dozen special lines were clearly marked at give-away prices. Peaches, oranges, bananas, apples, bags of grapes, pears; yoghort, slices of Gruyere and other non-fermented cheese; half a dozen different kinds of fruit tarts, wedges of rice-and-sultana cake; chocolate, sweets, biscuits. "Help yourself if you only a light snack and take it to the table" said the helper I'll come round and pick up the money. If you want something cooked, here's the menu, and I'll take your order right away." After only two hours' riding I was only needing a snack (and could have done without that, I suppose) and was away within 25 minutes. During my brief absence from the outdoor scene the three confederates of the night, Moon, Wind and Road, had passed a motion designed to make working conditions even easier on the next 43 miles shift to Laval. Twenty six of them to Mayenne took only 1 ½ hours, and here the truck drivers carried straight on along N12 while we turned southwards on N162. I say "we" because I now had got mixed up with a varied bunch of 20, which included a double-gents tandem. Most of them were my kind of Randonneurs, steady types who realized that however easy the going there were still nearly a thousand kilometres to go. Among us, however, were riders who had obviously started too fast from Paris and were beginning to pay the bill, yet still clung obstinately to their ambitions. One or two, I noticed, were beginning to get drowsy at the difficult hour of 0330. For my part I was beginning to settle down, a bit frisky even, following the wheels up the slopes and doing the odd spell up front along the flat. I did a spot of tandem-paced work, too. The "twicer" which had stopped for some reason, came back by me with a rush, in the manner of all such machines crewed by riders of moderate ability, slowed considerably on the hills. Whether it was the mechanism of the tandem that was at fault, or that of the crew I never discovered, but after a few miles with me on their wheel, they pulled up again. "Rien a faire" I heard the back man say. ("It's no good"). What was no good? He or the tandem? Probably the tandem. But I pedalled on smirking with satisfaction as if the Stoker was suffering. I was beginning to pick them off in twos. . . I rode into Laval with an old Paris-Brest-Paris man who knew that the Control was beyond the town on the road to Rennes. I thought back to 1965 when I followed Peter Hill on his winning ride in the amateur Grand Prix de France time trial which finished in this town, and then watched a professional Criterium in the afternoon. We now rode over one of the two bridges which had formed the turns of the small and picturesque circuits, which had also been the final lap of the time trial. In that 48 mile Grand Prix de France I had seen Peter Hill catch and drop Marcel Duchemin in his native village of Argentre, and remembered that the second fastest time of the day was made by a then unknown Spaniard whose name was Luis Ocana. Some Englishmen believe that Frenchmen live on frogs and snails, and some Frenchmen think Englishmen stop work every day and drink tea at five o'clock. At the Laval Control I was able to oblige my neighbours at table by enjoying a pot at 5 a.m., with a tomato salad and ham omelette. I recognised two riders who had rushed out of the Mortagne Control as I arrived, now fast asleep in their chairs before a half-eaten meal. I left Laval on my own. After her spell of night duty Matron Moon was settling down to rest and Dr. Sun was beginning his east-ward round. Our road had turned almost at right angles from N162 to N157. The wind, though still good, was not quite the help it had been. There was more company from motorised routiers for we were now on the highway between Le Mans and Rennes. Nothing much to report on the easy ride through Vitre except the steadily rising temperature and rapidly increasing volume of traffic making for Rennes, the capital of Brittany. On the outskirts of the city occasional escape from the mighty trucks was possible by taking to the compulsory cycle paths, and then it was a series of stops and starts at traffic lights and bumpy passages over pave before clocking in at the Control a few minutes after 8 a.m. Having dealt with a 5 a.m. pot of tea at Laval, I was ready for another with bacon and eggs. A plate of cereals would have gone down well, too. Rennes, however, was bottom of the Control League. Service slow, orders taken by personnel who went off duty without passing them on to the new shift, and finally nothing but cold ham and slabs of rice that tasted like cement. I wasted over an hour at Rennes where, to put the finishing touches to my frustration, I paid two francs for a bottle of Vittel water to pour into my bidon which I left on the counter. I didn't miss it until five miles out of the city on the road to Lamballe. It was along this 45 miles stretch that I caught and dropped Herbert Opperman several times. The sun was now well up, but I hadn't got a touch of it. It was over the matter of a photograph. The previous August "Oppy" had been one of the chief guests at the world championship dinner given by Pedal Club at Leicester, when my colleague Roy Green took a picture of him making his speech. Roy had given me a print to pass on to "Oppy" when I saw him next. I intended doing so at the start of this Paris-Brest-Paris and had the photograph in my handlebar bag. But that bag, you will remember, had been dumped in the U.S. Creteil van and I had ridden the first stage with almost naked bicycle. Since Mortagne the bag was back on the 'bars, the photograph tucked under the plastic map cover forming the lid. Until Rennes the following wind had tended to drive the picture into the cover, but now the route was going north-west the wind was on the side and doing its best to blow it out. It did, too, several times, but I managed to catch "Oppy" before he fell. I dropped him in the end, though, and had to stop to pick him up, dusty and a bit the worse for wear. A re-arrangement of the San-duff elastic prevented the Australian from breaking away again. While I was fixed on "Oppy" a rider of about my own age went by. I repassed with a greeting and seemed to be leaving him well behind when up he came on a hill. We got chatting and Monsieur Armagnac was a pleasant companion; that wasn't his name, but the district where he lived. But we were an unbalanced pair. I couldn't make out what kept him on the flat and he looked back on me from the heights wondering how on earth anybody could contrive to go so slowly uphill. He was a wine merchant. His helpers were at each Control with a bottle of something special. I would be his guest at Lamballe, he said. My immediate need, however, was for water or a fruit drink. There would not be much trouble getting that drink, I thought. Unlike the leaders who counted every second off the bike I could afford five minutes in a café, or even ten. I could see one ahead on the opposite side of the road. But the car park was so full that I decided to go to the next. Monsieur Armagnac and I continued our interval training, he working hard on the flat and resting on the climbs, I adopting the program in reverse. During neutral periods we chatted. My companion explained that he took part in many cyclo-sportif events over mountainous country and earlier in the year rode the famous Pyrenean trial which includes the climb of great Tourmalet and Aubisque passes. These little things I was complaining about were pimples, not hills, and Hardly worth changing down for. The kilometre-stones went by steadily, the sun climbed as easily as Monsieur Armagnac and the sweat poured off me. There are not many villages on this stretch of N12 and those that are have been by-passed. Not a café in sight. "Broons 10 kms" said a cross-roads sign but that again proved to be just off the main road. What with the heat, the night without sleep and 250 miles in my legs, I began seeing things. There on our side of the road, 200 yards away, was the café at last. Of course it was a garage, an oasis perhaps for the heavy truck routier, a cruel mirage to the pedaller from Paris. Monsieur Armagnac kindly passed me his bidon of water and said he thought I would be able to last out until Lambelle, now only 10 miles away. Then there on the left was a café and I bid my friend au revoir. "Your trouble is you drink too much!" he called out. He was wrong. My trouble is that I drink too little when cycling and that can be as foolish as drinking too much. Had I taken the bidon of water on the bike instead of leaving it on the counter at Rennes I would probably have drunk only half of it on the 43 miles to Lamballe, and then not because I felt thirsty but because I knew the body needed liquid. In the café I had a couple of glasses of Vittel water, a banana, and munched an apple as I started the last 10 miles of the "stage" which turned out to be fast and easy. I clocked in at 12-37 p.m. Already half-way

through his lunch, Monsier Armagnac invited me to join him and

his two helpers. I accepted only a glass of his wine which I

kept for the main meat dish which followed the plate of crudities--grated

carrot, diced beetroot, shredded celery, endive, tomatoes. I

left the cucumber because, in the words of an old Essex farmer

friend, "I like he but he don't like I" As I waited

for the dessert my friend hurriedly made preparations for departure.

A group of four were on the When the U.S. Creteil van had left me 180

miles earlier at Mortagne, M. Chambon explained that one of the

crew would be dropped off at Lamballe so that he could be of

help to any member of the team who had been delayed on the outward

journey and also be on the spot to look after anybody who might

be well ahead on the way back. Helper M. Baussant who was sleeping

upstairs as I ate, had left my box of odds-and-ends with the

Control official. Luckily I did not need another tyre, but took

a fresh bidon, all the remaining lamp batteries, the battery

shaver, two packets of glucose tablets, a bag of boiled sweets.

I stuffed them in the front bag, pumped up the tyres and pointed

the front wheel west. Then I noticed outside the Control a Clive Stuart

among the Uragos, Peugeots, Lejeunes, Singers and Rene Herses.

Whose was this very British bicycle? The official P-B-P number

tied to the frame did not carry a Union Jack as did those of

Davis, Parslow and Wadley. Perhaps a Frenchman who had been on

holiday south of The short stage of 32 miles to Guingamp provided us with the only glimpse of the sea on our journey to Brest. It was at Yffiniac Cove, an extension of Saint Brieuc Bay, but much more interesting than the peek at the briny through the heat haze was the corridor of onion bunches displayed on roadside shops and stalls. This is the district from which so many Johnny Onions set out for British ports, drape their strings of golden bulbs on hired bicycles and ride off in search of trade. Those who make Cardiff and beyond find that as well as the Onion being of the same family as the national Leek, the ancient Breton language and Gaelic Welsh are also closely related, and that seller and customer can carry on a passable conversation. Scores of British road racers now know this area far better than I, but when I first went there in 1959 Tom Simpson was probably the only British licence holder racing in Britanny. After I had tea with Tom and the Murphy boys whose parents had made Tom so welcome, they took me down the road to see the Saint Brieuc cement velodrome. I have since seen stages of the Tour de France finish there and have pointed the Stadium out to friends on the other occasions when passing along the Route de Rennes. But this time I just could not get my bearings. When the Onion country had given way to the built-up outskirts of Saint Brieuc I switched on to the compulsory cycle path and looked in vain for Tom's house and track. I followed the Toutes Directions signs into the town centre, bumped over the pave and climbed a gravel-strewn hill which made me anxious for those 9-oz tyres. Soon I was on the 50 X 16 building up speed for a down-hill swish round the ample shoulder of a ridge. This exhilarating free-wheel rapidly accounted for two of the 32 kms (20 miles) which separated me from the next Control. As well as being concerned about the tyres holding out, I was ever anxious about my personal wind and tubes. I was quite prepared for the next hour and a half to be something of a struggle, for a hot afternoon following an all-night ride usually brings its problems. Had I been 30 miles back along the road at that time, or 30 miles ahead, then I might have had a rough passage. Luckily the coast was not far away, and by the time they reached my hubs, the sun's bright spokes had been nicely cooled by a fresh sea breeze. Monsieur Armagnac had already been at the Guingamp Control for half and hour when I arrived. The Controller wrote 1600 on my Card. It was exactly 24 hour ago that we had left Paris, with 301 miles covered. M. Armagnac's helpers had found a shady spot and spread out a feast of food and drink in the boot of their car. After having my card stamped, I joined them for five minutes to sample pears and grapes, but this time would have none of his wine. Nor would I accept his kind offer to wait for me so that we could ride together to Morlaix. "Ride together?" I laughed "Some hopes. I believe this is the hilliest bit of the whole trip, and you're the last person I want to ride with. Get along on your own. I would only slow you down. I'm going inside for an omelette." "You eat too much" retorted Monsieur Armagnac who, you will remember, had also told me a few hours earlier that I drank too much. My defence to that second accusation is slightly different from that of over-drinking. I drank not because I was thirsty but because I knew the human tank needs filling up from time to time. I ate at each Control because I was hungry, and I was hungry because I ate little or nothing on the road. If I were 27 and not 57, then I certainly would have been in and out of those Controls like a shot, stuffing pockets with energy-giving foods for consumption in the saddle. But at my time of life, and with a target of just inside 90 hours, I could afford to eat well and slowly and at the same time rest my legs. Although most of my companions at the Control restaurant table were of similar mind, there breezed in the odd type who gobbled down a slab of rice and a couple of bananas, drank half a bottle of mineral water, poured the rest into a bidon, and was away in 10 minutes. In one or two cases I was able to give such fellows half an hour's start and catch them within 30 miles. The inference I hope you will draw is not that I was good, but that they were bad. Bad planners, that is; they were undoubtedly much better riders basically and would have left me standing if they had relaxed a little now and then. As I left Guingamp the first of the P-B-P official cars appeared from the opposite direction, which meant that the leaders were not far behind. On the way out of the town a familiar red-and-white van sped towards me, then pulled up on seeing that their Lanterne Rouge was showing up at last. From Beaumann the Wizard and Marcel Lejeune I got news of the business end of Paris-Brest-Paris. "Bonny of Marseilles was first to Brest in 20 hours 26 minutes, a record for the 375 miles. He had a 17 minutes lead over eight riders who included our fellows De Munck, Richard and Coulomb, but he has now been caught. You'll meet them in about half an hour. Don't forget-you sleep at Morlaix on the way back..." "Not me--but I think I can make Brest." I suggested to Marcel Lejeune that running a technical feeding van in Paris-Brest-Paris was like a double helping of Bordeaux-Paris. "Double?" he scoffed "You must be joking. Bordeaux-Paris is a holiday compared with this affair." "On the road you go" ordered the Wizard "You've got a few walls to climb between here and Morlaix, but they'll be twice as bad on the way back." "And against the wind too . . ." I sighed "No--they say the wind is going to change round and you'll be blown back from Brest." And with that we parted, the Flying Sorcerer and his apprentice Lejeune to prepare for yet another scramble at the Guingamp Control, I hoping to be driven up the Walls by the following wind. Many experienced Paris-Brest-Paris men having warned me of this Guingamp-Morlaix stretch, I had kept the 24 cog in reserve. It was to be used many times during the 34 miles. These Walls are crafty operators. They do not announce their intentions like honest hills by curving a little or a lot and showing you what you are in for, but disguise themselves as innocent, slightly rising straights. So they are for a couple of kilometres, then when you think it's all over the last 200 metres suddenly rear up like the banking of an indoor track. An illusion, of course. The excellent Michelin map shows only one 1 in 10 upward gradient on that stretch, but there must be a dozen just failing to qualify. Downwards, however there were plenty and I could see what Beaumann meant when he said the journey home would be tough even if the wind did change round in our favour. Official and helpers' cars were now coming steadily towards me, all with a friendly toot-toot of the horn. Then in the village of Plounerin I spotted in the distance the Peloton of leaders. I was on one of my down hill scampers and had to pull hard on the Mafacs to get a good look at the Aces plodding into the wind. Eight men still together, including three in the same Lejeune colours that I was wearing. They recognised their veteran team-mate and mutual cries of encouragement were exchanged. One official car was following, the only spectators two boys jotting down the bike numbers as they might have done on a railway line. How different it would have been had this been a professional race! That hill would have been lined with spectators; press cars in front of the riders and behind; radio and T.V. cars and pillion-riding photographers; a publicity caravan opening up the road a mile or two ahead, and maybe a helicopter buzzing and hopping around as well. If those two boys were checking position as well as taking numbers they would have recorded: Leading; Eight men. At about 168 kilometres riding in opposite direction No. 339, grey-haired old chap on red Lejeune. And if they stuck to the job until the very last rider had passed through on his way to Brest, they would be on duty for another 12 hours. As well as the tantalising Walls on the road to Morlaix there were several winding hills, well engineered but with surfaces torn and dented by heavy motor transport. The final one down into Morlaix could have been a free-wheel paradise on good tarmac, but was actually a furrowed inferno. I bet Barry Parslow was glad after all that he had left the trike at home! Morlaix was the busiest of all the Controls, with customers arriving from each direction, and the adjacent parking packed with helpers' cars. My own U.S. Creteil van was there awaiting the return from Brest of the three men who were due to sleep for three hours. There, too, was Patrick Debruycker whose father Louis was back from Brest and already between the blankets. Louis is an old friend who for many years was personal mechanic to Jacques Anquetil in the Ford and Bic teams and was also regularly called up for service for France when the national team formula was in operation. Two or three years ago Louis retired from this hectic life to run the family café at Lille, and began cycling again (he was a useful pro. before turning mechanic). At the start of P-B-P he told me he hoped to beat 60 hours and there at Morlaix he was well inside his schedule. So was I, and before checking at the Control I was able to do a bit of shopping--a couple of small torches of the throw-away-when-finished type and a spare T-shirt. At the Control I found contrasting types sharing the same restaurant table. Outward bounders like myself taking it easy, some writing post-cards and reading the papers, and those heading for Paris attending strictly to the business of eating and drinking and thinking only of getting back onto the road. My helpers came in from the dusk, urging me to hurry with my meal and ride for half an hour before lighting up. It was gone 8 o'clock when I set out, just as one of the U.S. Creteil boys came in. He said he found the last stage to and from Brest hardest of the lot. For my part I was to find it one of the easiest and most enjoyable. Well rested, well fed, well clothed, I switched on the lamps after steadily climbing the big hill out of Morlaix, to be seen rather than to see, for Matron Moon was back on duty again and the western sky still glowed with the memory of the departed sun. After the heat of the day it was pleasant pedalling along the undulating N12. After eight miles the multi-red lights of a passing truck rose gradually in the distance, then reared abruptly for a minute or so before being extinguished from my view by the crest of the hill. That was obviously the first of the two 1 on 7 climbs I had spotted when looking over the map at Morlaix. I rode most of it, walked the rest. Why not? In my younger day I would have been ashamed to admit such a thing. On my present mission it was the right drill. Riding the lot might have strained the muscles which so far I had preserved by careful riding. In track suit top and bottom I would have seated and then cooled off too quickly in the freshness of the night. So I walked slowly and quietly up the hill. I walked quietly because I had no metal plates on the shoes which weren't cycling shoes at all but a pair of old Hush Puppies. My conversion to this type of footwear for all cycling but racing dates back to a long-distance raid I made on a borrowed bike in 1967. Starting at 5 a.m. and wearing cycling shoes fitted with plates, it took me 10 minutes to realise that one pedal carried a short toe-clip and the other a long. It took another 200 miles to find a shop with a pair of medium clips to which I was accustomed, by which time the big toe on the short-side had become red and swollen through pressure on the clip. Next day I could not get the shoe on, and had to wear a new pair of Hush Puppies carried in the bag for evening use. The going was

fast and easy through well-lit Landivisiau where a group of eight

coming from Brest called out a cheery bonne route. In

the distance I saw the red lamp of a fellow traveller and expected

to be with him before leaving town. On the next cross roads was

a "Diversion Brest" It was a happy meeting, each of us with something to offer the other. He was a lad who was in need of company, I was in need of light. I had realized that if I had enough miles in my legs for Paris-Brest-Paris I had not brought enough batteries, and was trying to make them last as long as possible. For 10 miles we saw little of the moon, our misty road running through a tunnel of trees in the Elorn valley. My companion was an experienced Randonneur who cheerfully accepted his role as a path-finder, switching over to dynamo lighting in the darker patches and down the hills. Occasionally in the open stretches we rode along together and talked. He was a native of Saint Brieuc and had seen Tom Simpson in his earliest races. He solved the mystery why I had failed to spot Tom's old house and the velodrome on the Saint Brieuc; we had entered the town by a new road parallel with the other. We stopped at a café at Landeau for a drink of hot chocolate, leaving at 11 and reckoning we could make the 13 miles to the Turn by mid-night. Outside the town the road turned sharp right, away from the Elorn which had now widened from River to Estuary, and made for Brest over the second of the 1 in 7 hills which I rode. My companion waited for me at the top, set the dynamo spinning on the subsequent descent and then back to battery power for the rest of the stage to Brest whose own lights we could see beckoning from the lower distance. All Controls had so far been easy to find. One simply followed the road towards the next known town and there was the café of hotel on the route itself. The approach to the Turn at Brest, however, was more complicated, and we had been given a detailed sketch map at Morlaix. Mine remained in the pocket of the bag. My companion had been that way before, and with him still leading we waltzed round the islands and corners, glancing up at the clocks with satisfaction. Six minutes to mid-night it was when we free-wheeled, two abreast to Brest and found ourselves a space for bikes outside the Control in the Boulevard Gambetta. We clocked in six minutes short of 32 hours after leaving Paris 375 miles away and were, an official said, the 172nd and 173rd riders to arrive. "Where do we sleep?" asked Saint Brieuc. I'm afraid you don't. . ." The official was genuinely concerned at having to impart the news "All the sleeping space is taken. Not a square centimetre anywhere. . ." In moments of crisis like this there is only one thing to be done, even at midnight. A pot of tea. And over the cup in the bar le Breton and the Gt. Briton discussed the situation. I was all for having a smack in the restaurant and then getting back to Morlaix, but he reckoned something could be arranged, and went off to make further enquiries. He was soon back with an official who was hopefully dangling a bunch of keys which he believed would open the door to a lounge where (he had been told) there were easy chairs and a settee. None of the keys would fit. Eventually he found us three small cushions apiece, led us to a dimly lit room whose floor was covered with bodies. By what I though at the time was a happy chance, two sleepy figures were groping for their shoes, and after they had picked a way through legs and bodies to the door, we went through the same exercise to occupy the vacant spaces. The previous occupier of mine had been a shortish fellow, and by the time I took up residence the next door neighbour had rolled over to reduce the area by half. I squeezed into the little plot, tucked up my knees, closed my eyes. Unfortunately I could not close my ears. All round me were snores whose performances if put on tape and concentrated into one big roar would have silenced foghorns in the Rade de Brest. On the other side from the man who had pinched half my space was a calculating villain of a different kind. In his sleep he was working out average speeds between Controls, and every now and then would mutter Soixante-quinze heures (Seveny five hours). I lay there for an hour without sleeping, but my eyes closed. Then I got up, had a leisurely shave and wash, went down for a 3 a.m. breakfast of soup, omelette, bread butter and jam, and an unusually strong pot of tea. Also eating was a character from the south of France I had come across at various Controls on the way down from Paris. Each time he called me "neighbour", insisting that I lived at Carcassonne. I had given up denying this. This time he had wisps of straw in his hair and more sticking to jersey and shorts. He had dossed down in man's primitive bedding for a couple of hours and was now eating like a horse. It was just 4 a.m. when I left Brest after a total stop of four hours.... |