|

So there I was, mission accomplished, tucking into yet another meal, and with half a bottle of wine in celebration. I was well inside the 90 hours target and in a way glad that I hadn't beaten 80, for that would have meant finishing at mid-night, a lift to my Paris hotel, a sleep until midday and missing a lot of fun. At the odd hour of 0330 I was in no hurry, sitting around talking over experiences with other finishers and watching "slower" riders than ourselves clock in. Some were probably much faster than us really, delayed in one way or another. Certainly there was a good Samaritan or two among them who had crossed the road to help a comrade in distress and nurse him back to Paris. Most of the party gathered in the café-restaurant

of the Croix-de-Berny stadium were in need of a wash and shave

and sleep, but one young fellow was fresh and well-groomed. Yet

he, too, had ridden the same distance as us, though very much

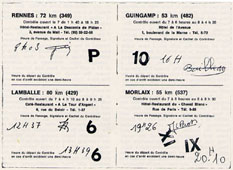

faster. He was friend Jean Richard who had "Little Herman De Munck was too strong for me" he said" "He dropped us about 20 kms the other side of Rennes and we never saw him again. I perhaps could have finished second, about three hours down, but was content to stop with my friend Pierre Baleydier." An official kindly turned back a page of the finishing sheets until I found that Barry Parslow had finished in 73 hours, like me three hours behind his most optimistic target. His early fall and painful arm no doubt would have been a great handicap. He was certainly a hero in my eyes to get round so well with all that baggage. I wondered how the even heavier-weighted George Davis had fared. He was, I supposed, behind me from the start. Was he one of the lone pedallers I had met after turning in Brest? There were, I was told, camp beds in another part of the Croix-de-Berny stadium and a friend offered me the freedom of his comfortable van for a kip, but the unique atmosphere of the Last Control was too good to miss. I found a seat in a corner and dozed, coming back to life every now and then as fresh arrivals clocked in. Some were fresh and lively, others the worse for wear; one glowed with satisfaction at getting there and back in 86 hours, another growled at missing his target by as much as 12 hours. As one dejected soul explained his downfall to a pal I must have dozed off, and when I stirred it was half past eight and time to 'phone the wife and report my safe arrival. An official said there was a post-office open just down the road, but on checking that with the gendarme outside it turned out to be more than a mile. I pumped the front tyre and set out to find it. That 756th mile to 'phone and the 757th back along a level road were the hardest of the lot. Back at the Control they were still coming in with less than an hour to go. Again, there were riders of moderate ability who had wrestled desperately against fatigue during the night to beat the clock. On the other hand, Jean Richard explained, there were odd characters who could have been in hours ago but had been hanging around in cafés in order to get 89 hours and a large number of minutes engraved on their medals. It takes all sorts to make the world of Randonneurs. When I got back from my hard ride to the Post Office, the sun was well up. It was pleasant lounging in the courtyard watching riders still coming in, chatting, and looking round at the interesting variety of bikes. And there it was again, that Clive Stuart I had seen at Lamballe on the outward trip, and this time with the owner attached to it as well. He was tall, as I expected, and speaking French to a friend. I asked him in that tongue why a Frenchman should be riding an English bicycle. "I'm not French" he replied "I'm as English as you are, from Orpington Kent. I'm working over here, and a friend suggested I did a bit of cycling for exercise. When on holiday at home I looked round for a bike and brought this Clive Stuart back with me. I'm glad I did; the finish is much superior to that on most French models. I was very satisfied with the way it stood up to this test. I'm pleased at getting round inside 90 hours, too. I did 86-9". Colin Phillips had answered one question that had intrigued me at Lambelle. Now he was about to answer another that had been with me most of the way round. What was he doing in France, and where did he live? I asked. "I'm doing medical work and I live at Carcassonne. . ." Around me were other answers, too. What had happened to Monsieur Armagnac? Had he finished hours ahead, and was he now well on the way back home by car? Not at all. He finished after me! Instead of having but three hours sleep in the hotel at Brest--where he had offered to book me a room--an unreliable alarm clock had treated him to eight! And Dr Graves? He, too, was there at the finish, but unfortunately had not completed the course. He and his fellow Californian Ruby Curtis made a bad start by going off course during the first night and riding an additional 25 miles. This was not only bad for the morale, but landed them up in the worst of the heavy truck traffic in the Rennes area where they eventually retired. "But the experience was useful" says Dr. G. "If I ride again in 1976--when I will be 70--I'll make sure I have my 19 lbs bike with me. This time I had a 30 pounder which I was going to use in the Tour of the Pyrenees. I'll have warmer clothing to put on during the night--we don't get such low temperatures in southern California where we come from. Unlike you who went it alone, I like plenty of company and hope next time to persuade more friends to come along. My advice to them will be to have plenty of big red back lights to frighten off those trucks." I kept an eye open for George Davis, not knowing that he had arrived (in 87-47) just before I had made that 'phone call. Then I delivered the tattered photograph to "Oppy" who had arrived with Lady Opperman to preside over the after-race Reception. They were both delighted with their visit. Oppy had been down a memory lane 755 miles long, reliving his epic of 1931. This time he saw quite a bit more of Brest where the city honoured him with a civic reception, and he ate more leisurely while getting there and back than 40 years ago when food and drink were snatched from musettes and battered metal bidons. He had to look hard to find the few remaining stretches of the dreadful cobblestones that had shaken him to bits in Rennes. Oppy won that 1931 Paris-Brest-Paris in 49h 23min. Now he was congratulating Herman De Munck who covered a slightly longer distance in shorter time. The Australian used a single 47 x 18 most of the way, switching the wheel round to the 16 tooth cog for the final sprint at Paris. De Munch used a triple chain-wheel giving 15 instant gears between 53 x 13 and 45 x 22. The Australian

guest of honour was full of admiration for the hard-riding cyclo-touriste

class he was meeting for the first time. His French being rusty,

the essence of his speech was interpreted "I was a professional cyclist" said Sir Hubert "I lived by the bicycle. You fellows are real cyclists. You live for it." Looking back over my ride I think I was a bit too cautious. Better, however, to be safe than sorry. If you start too fast in a 12 or 24-hour time trial and then blow up, at least you can have another go next year, or even the same season. But Paris-Brest-Paris comes but once in five years and my anxiety to avoid a "parcel" in my first attempt was prompted by the fact that in 1976 I shall be 62 and perhaps not in good enough condition to tackle the job again. I probably could have finished inside 80 hours had I made small but regular reductions in the time spent at the Controls. I must have been off the bike for 22 hours in all. With only a quarter of an hour trimmed off at each Control stop my total time would have been down to 79 ½ hours. This saving could have been carried out without affecting my form when back in the saddle, but to have tried to pinch another10 minutes each time would, I am convinced, have been a bad move. In an event of this length self-knowledge is of vital importance. We often hear the expression "that man does not know his own strength". Between 6-10th September 1971 I saw many men who didn't know their own weakness until too late. I am glad that I knew mine in advance. I started the trial because it had long been my ambition to ride over the famous route in the semi-racing conditions of the Randonneur event, and I knew I was in good enough shape to do the job inside 90 hours without taking too much of a hiding. On the way out I averaged about 14 ½ m.p.h. for 26 hours actual riding, and 10 ½ m.p.h. for coming back into the wind. During the return journey my tendon, knee, seat and hand troubles were laughably light compared with the agonies suffered by others. One member of the U. S. Creteil has written in his club magazine that 15 of the 25 miles between Mortagne and Verneil took him nearly three hours. His total time from start to finish was 8 ½ hours faster than mine--and he had already built up 8 hours of that at Brest, half of it because he was that much faster, and half through rushing in and out at the Controls. I certainly cycled back from Brest faster than this clubmate, enjoyed nearly every minute of it, and didn't have the slightest trace of back-ache. In the month before the trial I took a

multivitamin tablet at breakfast, and once "on the road"

to Brest treated myself to an extra one at night. These were

supplemented at each meal with two 50 mg Vitamin C. pills. I

made sure of not exceeding that dose by carrying only the bare

ration in a I had always imagined myself sleeping solidly for a day after such an adventure. In fact after the pleasant open-air ceremony which I have already mentioned, there was a Champagne Reception in yet another room of the vast Croix-de-Berny stadium, and following that a small luncheon party given in honour of Sir Hubert and Lady Opperman. I'm afraid I nodded off a bit during the latter function, but Oppy knew the feeling! From there we had to hurry back to the Hotel de Ville where Sir Hubert was presented with the Silver Medal of the City of Paris. It was during the Hotel de Ville party that I noticed my ankle--though not painful--had swollen considerably and was beetroot red. Fortunately there was a distinguished Doctor in the house in Clifford Graves who understands such matters, falling a victim to them himself on occasions. While guests and hosts left the chandeliered chamber for a tour of the City Hall and a splendidly uniformed official hovered round with the keys ready to lock up, I lounged back on a throne-like chair with trouser-leg up, and Dr. Graves made his examination. Strain of the Achilles tendon, he said. It would pass off in a few days, although the redness could mean that the pain would be more intense tomorrow. He added that the numbness in the hands and fingers would take longer to clear. (He was right about the hands; two months later the left little finger was still not quite right. Next day, however, the ankle swelling had gone down, though the area remained red and tender. I then realised that I had not told my Doctor all. I had quite forgotten that when the pain first came on after breakfast at Morlaix, I thought heat-treatment might help and rolled down the right sock as far as it would go. The sun first shone on the ankle from the front, then moved right round in a nine-hour semi-circle to give it a thorough grilling. It was cooked for the same period next day. I had invented a new cyclists' maladay: overdone Achilles tendon.) Dr. Graves then went back to his hotel to prepare for a night train journey down to Montpellier where he would join a party of friends for the American Bicycle Society's tour of the Pyrenees. I went with Wizard Baumann in his car for yet another Reception, this at the Lejeune Cycles headquarters. More champagne. I left at about 9 p.m. to take the Metro to my Hotel, four stations and no more than five minutes away. When I woke up I was four stations beyond my destination. I crossed on to the reverse platform and boarded another train, went to sleep again, this time overshooting my station by only one. I stood next time to make sure. Soon I was in the bed I had occupied five nights ago, since when I had slept solidly for only 2 ½ hours. At the risk of

being labelled a bore I have dwelt at length on my own moderate

performance in There are probably 200 eligible British club riders who would easily get round in the qualifying 90 hours, 100 inside 80, 50 inside 70, 30 inside 60 and ten inside 50 hours. Please notice the qualifying word "eligible". Only riders who had not held a racing licence for at least three years were accepted and there is no reason to suppose it will be any different in 1976. Superb time-trial-cum-roadmen like Robin Buchan and Roy Cromack would therefore not have been eligible in 1971, although veterans such as Nim Carline and Cliff Smith could have ridden; so, too, could near-500 miler Eric Matthews who has not had a racing licence for several years. As for Beryl Burton, well, if she decided not to take out a licence after 1972 but continued time-trialing, she could have a grand time thrashing t'lads from Paris to Brest and back. The present women's record of 62 hrs 3 mins was set up in 1961 and Beryl might be interested in trying to lower it by half a day. She might even talk husband Charly and daughter Denise into riding, too, and establishing a unique family performance. There are several team cup and shields offered in Paris-Brest-Paris which would interest British clubs. Not until the event had been over for more than a month did I learn that in one section I was the third counter in the U. S. Creteil team, although my 83-22 was the slowest of the six finishers. I have mentioned my several requests to the Wizard for an explanation why I had been transferred from Colchester Rovers but found him too busy to reply. (He has since claimed that he did tell me when driving to the Hotel de Ville reception but that I had gone to sleep!) One of the cups

was presented by l'Equipe and awarded for the best aggregate

time by three members of a club, two of the counters being under

25 years of age, and the third over 50. The U. S. Creteil had

several entrants in the first bracket, and one veteran, Pierre

Rebillard, father of Daniel who won the Olympic pursuit championship

in Mexico. Rebillard pére rides regularly in veteran

trials and was very fit, his preparation including notable rides

in the 160 miles Brevet In contrast to my cautious attitude on the actual job, my approach to the adventure was somewhat casual, particularly with regard to the machine and equipment. The idea of arriving in Paris with an almost new saddle, putting it on to a brand new bike and setting out on a 755 miles ride horrified some of my new clubmates. Borrowing bikes in odd places is, however, something of a hobby and I have tamed some pretty awkward mounts in my time. For 10 years my wife and I have made holiday bases in the West of Ireland, hired heavy and sometimes grotesque machines from shop, store and bar, and had a splendid time pedalling around that countryside. And I must tell you about the 1970 Christmas we spent with her police-sergeant brother and family in West Wales, and accompanied by our friend Mal Rees. On Boxing Day

a 14 year old nephew suggested a ride on the bikes. From the

cell of Towyn police station we released a long abandoned mangle-on-wheels

last ridden by a Sergeant in the Which is a roundabout way of saying that I would have tackled Paris-Brest-Paris on any reasonable kind of bike, and was therefore prancing with delight at the idea of riding a thoroughbred from the famous Lejeune stable. Looking back now that it is all over, and if the ride were to be repeated next year, I would make one or two small changes. Instead of the Cinelli racing 'bars I would have a pair of Randonneurs which give a restful cruising position on their slightly "cranked" tops. Although it is possible to fix a stiff-framed front bag forward between the bends to leave the straights free for a "knuckles-up" grip, I would carry my luggage behind, leaving the little carrier in front to take maps and route instructions in a plastic case. I won't be doctrinaire over this matter of air resistance, however, and am ready to be convinced--as a friend has already suggested--that a front handlebar bag simply stops air instead of the body. I remember a chat with a fellow in the Croix-de-Berny courtyard just as the Control was finally closing. Yes, he said, the front bag could be a handicap in strong wind, especially if it were coming three-quarters-on. But the pros. outweighed the cons. With those quick release elastics to pockets and main compartment, everything is readily available. A man can feed as he rides, consult maps and papers, slip on gloves and extra clothing if necessary. Many in fact do that in the higher levels of these Randonneur events in which losing contact with the peloton can be just as serious as in a conventional race. I deliberately

kept the gears down, with a top no bigger than 84 (50 x 16) and

the bottom 47.5 (42 x 24). Next time I would use a triple chain-wheel

to supply an over-drive for the fastest stretches and have something

in the mid-30s for the Walls on the Côtes du Nord and Finistere.

I would, of At my speed I don't think there is much to be gained by using tyres light enough to win the B.A.R. and might even settle for sleek wired-ons so that the dynamo could be used downhill without risk of an explosion. Moreover ultra-light rims such as I was riding are fine so long as a new wheel is readily available should one take a heavy knock. Something else, too. We were lucky in having such glorious weather all the way through--I doubt if I saw one cloud in the sky. In one Paris-Brest-Paris, I learned round the Control tables, there was heavy rain nearly all the trip. In such conditions I would feel more comfortable on fatter tyres with a bit of a rib on them. With all that heavy traffic on N12 there were frequent patches of oil on sun-baked tarmac. Add rain-water to that and one could be in trouble with light, narrow bands of smooth rubber, especially during the night. French cyclo-touristes have long been telling me that one could write a book after riding Paris-Brest-Paris. I nearly have, and it would have been twice as long if I had gone round deliberately collecting material. I made no notes during the trip, but memories keep flooding in every time I sit down at the typewriter. More than 250 others will have different

stories to tell. Barry Parslow, for instance, has since told

me how he badly wanted another spell of sleep during the last

200 miles, but plodded on so as to be able to catch the night

train home. When I mentioned that this was the most sporting

event I had ever ridden he said I wouldn't have thought so immediately

after his crash when riding with a big group. Others fell, too,

and after sorting themselves out the victims tore off in pursuit

of the chap who caused the pile-up and had ridden calmly on.

There was a mass unclipping of bicycle pumps and a few dozen

of the best were administered to the culprit's back and bottom. And what about the seven super-cyclists who finished the P-B-P Audax controlled-speed ride on Sunday night and then started next afternoon to do the 755 miles all over again as Randonneurs?. The best of them, R. Plaine did the second round trip in 55h 42m, 24th of the 271 finishers. The story I like best of all is that of a man who was doing a really good ride of around 65 hours when he stopped to make some minor adjustment in a village. He then sat down for five minutes for a breather and . . . fell solidly asleep. He was found stretched out by locals who notified the police who summoned an ambulance which conveyed him 45 miles to the finish at Croix-de-Berny. Later, and much more wide awake, he persuaded an official to drive him back to the village where he had "abandoned". His bike was still there, and on it he pedalled back to Paris to finish well inside the 90 hours. |