This is a version I presented as a ’Special Interest Session’ at the ’Ski For Light’ annual International. Ski For Light is a story unto itself. (More information at www.sfl.org)

___

Back in the 1970s and 80s I was an OK bike racer. I finished races, but never won. I eventually found that I preferred noncompetitive rides that were a bit slower and longer than most races. I rode with friends or alone, sometimes even at night, experimenting with a variety of lighting systems. Then I heard about a series of 'brevets,' long rides that would qualify me for another ride in France, about which I knew nothing. I was most interested in the brevets just to see how far I could ride in a day.

The cyclists among you will know that a 'century' is a 100-mile, one-day ride. The title of my story refers to that meaning of century, and to the apparent age of some of the villages I rode through in northern France.

I apologize in advance that you'll have to hear me sing, but it will be only once, and it will be over soon. I don't intend this story to be a pat on the back. It's really just a story of a very quirky, very French, bike ride.

David Fisk

___

RIDING INTO THE EIGHTH CENTURY

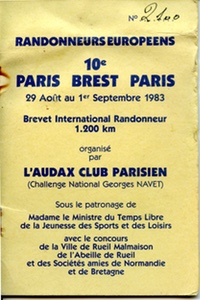

Paris Brest Paris 1983

Copyright David Fisk

"Alouette, gentil Alouette, Alouette, je te plumerai" drifted into a warm Brittany night. Then, another group of cyclists began from the back of the pack, "I've been working on the railroad...." Until we ran out of songs-which didn’t take long--French and English tunes, sung badly, rang out; it's one way to stay awake a bit longer on a long late-August night in northern France. Six Frenchmen, a Canadian, and four Americans had formed an alliance against increasing fatigue. We were among 1100 riders, including 74 women, several tandems, and even some tricycles, who had started the 750-mile Paris-Brest-Paris Challenge 44 hours earlier, and we were gaining on the 500 mile mark. Some of our small group had slept a few hours the night before and would sleep again tonight, but two hours of riding remained before our next stop, the Loudeac checkpoint, where food and beds awaited us.

Those unfortunates who rode without company to help them stay awake tried to focus on spots cast by feeble headlamps, but occasionally veered off course to a prickly awakening in the nettles that lined the roads (and made nature breaks something to remember). Some riders slept in phone booths, doorways, haystacks and barns when the hills and distance of what is probably cycling's largest event (based on total rider miles) took their inevitable toll.

Paris-Brest-Paris--PBP--was the 1891 conception of Paris newspaperman and cyclist Pierre Giffard. Concerned that the bicycle might go the way of the self-tipping hat and other wonders of the Industrial Revolution, Giffard wanted to demonstrate the bicycle’s ability to increase the distance and speed with which a human can travel on muscle power alone. He proposed a ten day tour from Paris to the Atlantic coast city of Brest and back. But Dunlop and Michelin, makers of the new, and controversial, pneumatic tire, saw in PBP ten days of free publicity in the sporting newspapers and gave full financial and technical support to their riders. To them it was a race, and an advertising windfall.

The professional Charles Terront finished the inaugural Paris-Brest-Paris in 71 hours and 22 minutes, less than a third of the time Giffard had estimated. Bear in mind that in 1891 a paved road might be a thousand year old cobblestone leftover of Roman France, the "pahvay” for which today's Paris-Roubaix race is famous. Likely, many rural roads weren’t even that good. And the single-speed bikes of the era probably weighed three times that of today’s 15-pound “fixies.” Terront's performance was probably a much greater effort than riding a modern mountain bike 250 miles a day for three days.

PBP's popularity with cycling fans convinced Giffard that it was worth repeating, but only at ten year intervals--perhaps at the request of the exhausted riders. Professionals dominated the race in 1901, 1911 and 1921. In 1931, to offset a decline in professional entries, a new category was added, the "Randonneur." Sixty of these hard-riding long distance cycle-tourists turned out to test themselves against the new 90 hour time limit. On a fixed gear machine weighing nearly thirty pounds, amateur Jules Tranchant turned in the time of 68 1/2 hours. Even today that would put him in the top 15 percent!

World War II pre-empted the 1941 edition of PBP, but it was revived in 1948 as an all-amateur event. The randonneurs viewed it as the ultimate achievement. Roads, bicycles, and riders improved, and so did the fastest times, but for the majority, the challenge remained simply to beat the time limit and to be listed in the official record of the event as an “Ancien,” a veteran, of Paris Brest Paris.

PBP’s format is essentially unchanged since 1948: 1200 kilometers (750 miles), from Paris to Brest and return. A 90-hour time limit. There are mandatory checkpoints, both announced and secret. Stops for meals, sleep, and any repairs are included in a rider's total time. Qualifying rides of 200, 300, 400, and 600 km are required to help riders prepare for 1200 km. To emphasize the amateur nature of the event, bicycles must be equipped with full fenders. Night riding is essential to finish in 90 hours, and some of the checkpoints are open only at night, so head- and taillights are required. Support vehicles are permitted but they must follow alternate routes and may meet their riders only at the checkpoints, which are usually separated by about 50 miles. Although most riders choose the 4 a.m. start, they have the option of a 10 a.m. or 4 p.m. start to allow them a few fitful extra hours of sleep--but their 90 hour limit is reduced accordingly. In 1971 the interval between events was shortened to four years.

I rode in 1983, with no support vehicle and no organized group, a bit unusual, although many of the sixty Americans rode the same way. Everything I thought I would need for 90 hours, other than food and liquids, was in a handlebar bag, under the seat, or in my pockets. I traveled as light as I could. No rain gear, no jacket, no long pants. I hoped for dry weather. (I was damned lucky.) I chose the 4 a.m. start to give myself the full 90 hours to finish.

Day 1

Escorting the 4 a.m. starters from the Reuil-Malmaison Stadium, and controlling intersections until daylight, were a multitude of crisp "gendarmes" of the French Republican Guard aboard matched  BMW motorcycles. But as helpful and efficient as they were, they had little control over non-Francophones. At one crossroad, a well-known American rider mistook "a droit!" ("Right!") from a white-gloved officer as "Good luck!" and rode straight through. BMW motorcycles. But as helpful and efficient as they were, they had little control over non-Francophones. At one crossroad, a well-known American rider mistook "a droit!" ("Right!") from a white-gloved officer as "Good luck!" and rode straight through.

As riders strung out, a delicate thread of glowing taillights disappeared and reappeared in the rolling hills. It was quite beautiful--to a cyclist who enjoys night riding, anyway. For hours, the miles-long peloton drew a tunnel of air along with it like a railroad train--the perfect draft.

Arriving in the medieval town of Nogent-le-Roi at 6:30 a.m., I couldn't tell whether a surprised milkman doubted our sanity, or just wondered how many of us would survive to pass through on the return trip in three days. But each village was a little more awake than the last, and soon we were treated to a particularly European phenomenon: genuine fans lined the route, smiling, waving, offering water, calling out "Bon courage!" Children held homemade signs declaring "Les Bretagnes vous encourage!" For the American cyclists this welcome was an unexpected treat.

My goal the first day was simple: I wanted to meet and ride with a hero, Lon Haldeman, the aforementioned well known American rider, who had twice won the 3000-mile Race Across America. Then I would deal with the rest of the ride.

It took a while for the several hundred 4 a.m. starters to squeeze from the starting area onto a narrow street, so, being among the later starters, I guessed Haldeman was somewhere in front of me. My adrenalin flowed, and I began passing every group I caught. I'd pull onto the back of a group to draft and rest, move up to the front, and if Lon wasn't there, “à bientot" (see you soon!) By the time I caught him, outside the little village of Ormoy, Lon’s 18 mph pace was about all I could handle. I pulled in behind him and ‘sucked his wheel’--drafted--for a while. But we rode side by side some, and chatted a bit. He commented on my bike’s small cogs, not the best for climbing hills*. His bike carried four bottles, panniers, and had a generator dragging on the front wheel, but he seldom used the small chainring. He was on a Sunday ride; I was on a schedule to set a personal record for a century. [I did: 5:50, 17 mph.] (*In Paris I had swapped a 13-24 5-speed freewheel for a 13-21 6-speed. I guess I thought a 5-speedwas too old-fashioned.)

After 95 miles on only a liter of water and little food, I was definitely suffering dehydration and electrolyte imbalance--the dreaded ‘bonk.’ Lon filled one of my bottles from his, then dropped me on the climb to the first checkpoint, in Belleme. But I can now say Lon was my ‘domestique,’ and I was his. When he had made a wrong turn in the dark, I had chased him down to get him back on course. his. When he had made a wrong turn in the dark, I had chased him down to get him back on course.

At Bellême, whole families had turned out to see the procession of cyclists. They watched as we had our control cards stamped, filled bottles and pockets, and made our way down the narrow streets from the checkpoint back to the main route. It was becoming apparent that competetive cyclists (even if they’re racing only the clock) here are more akin to national heroes than just obstacles to motorists. And to have come from America to ride through their little town, "c'est bon!"--it’s good!

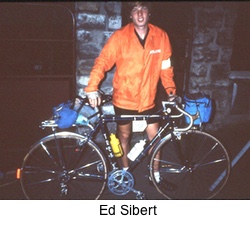

The official record of PBP 1983 says that I was the first rider to reach Bellême. Two other riders, Americans Ed Sibert, with whom I had ridden my qualifying brevets, and Haldeman, arrived ahead of me, but they had ridden so fast that the checkpoint wasn't scheduled to open for a few minutes. To make use of the time, Ed and Lon went looking for food and filled their water bottles. I rolled in the moment the checkpoint opened, while the two faster riders were still foraging. A fluke of PBP timing had put me in the lead. But the distinction was short-lived. With food and water in me, and back on the road, I slowly recovered from the bonk, while many riders I had passed earlier now left me in their wakes. My “see you soon”s were more prophetic than I had realized.

Another problem was that I had never investigated northern France’s topography. I had heard about difficult climbs at 300 and 450 miles into the ride, but nothing about the almost endless succession of 300 footers. After 150 miles of them I longed for the 24 tooth gear on the floor of my

dorm room back in Paris.

Most of the American riders had developed tasty and energy-packed long-distance diets during their qualifying rides in the US. I relied heavily on peanut butter, ham and cheese on raisin bread. In France we had trouble even locating grocery stores--the French word ”Épicerie” doesn’t exactly

say ‘get food here.’ By the second checkpoint, at 150 miles, my sandwiches of runny Camembert on crusty bread were starting to lacerate my mouth. So I took advantage of that checkpoint's "self"--a cafeteria--and ordered what appeared to be the national dish, a delicious cheese omelette with a heaping side of green beans. The French invented the omelette, and they deserve the credit. At that point I knew that the dried apricots I carried, water, and a candy bar would carry me the 50 miles between checkpoints as long as I ate something substantial at each stop. The record books, for me anyway, would have to wait until the next PBP.

At the Fougéres checkpoint I bought some Vichy water. Real water quenches your thirst, replaces lost fluids, and can be swallowed. The highly carbonated Vichy, on the other hand, is sour, goes down like liquid firecrackers and doesn’t replace fluids if you don’t swallow it. It's probably good for disinfecting cuts. Thereafter, I ordered my water "sans gaz" (without gas).

Robert Lepertel, PBP's perennial director, designed a route through Fougéres to bring us past the village landmark, an ancient fortress, complete with drawbridge and a properly unappealing gunk- filled moat. This fortress probably hadn't had so many Anglo-Saxons at its walls since Britain’s Henry VI and his army "visited" the place in 1449. This time, however, we are somewhat more civil. filled moat. This fortress probably hadn't had so many Anglo-Saxons at its walls since Britain’s Henry VI and his army "visited" the place in 1449. This time, however, we are somewhat more civil.

In the evening, at the Tinteniac checkpoint, a young future randonneur waits with pen and autograph book. I sign somewhere below Haldeman's name, grab a quick bite, and settle--gently--onto what had once been a tolerable saddle. Night falls as I struggle the fifty miles to the Loudeac checkpoint. In 21 hours I’ve ridden 285 miles, setting a personal century record and fighting the bonk along the way. The goal of a triple century seems to have lost its importance. Food and sleep win the imaginary coin toss. The fact that Loudeac has real beds for riders kind of colors my decision. My plan to sleep as long as six hours surprises the checkpoint's wakeup crew, but it gets me to daylight and saves me a soaking in the first of PBP's two downpours. At 7 a.m. a voice reminds me why I have come to France. "Oui, merci," I say. Anything to make it go away. 7:05: the voice is back in a more insistent tone, probably because someone else needs the bed. I gather my handlebarbagful of belongings and step out to the still wet courtyard of the boarding school-turned-checkpoint. Lynn Cox and a handful of soggy Americans who have ridden all night pull in, but the rain is the least of Lynn's concerns. One of her knees is acting up. Tomorrow, after riding 535 miles, the pain is so great she can’t turn the cranks. Her decision to drop out of Paris-Brest-Paris is not easy. [On a happier note: in 1991, Lynn again qualified for PBP and completed it.]

Day Two

Today my theme is NO THEATRICS. Ride steadily, practice my French, enjoy the scenery, eat well. Pull onto the back of a pack, move up through, chat a little, do some work at the front, “à bientot," and on to the next group. Many of the riders I pass haven't slept at all and are not exactly setting the highway on fire. Eventually I find a group of six Frenchmen riding a reasonable pace and join them--for thirteen hours.

They represent a club from the city of Achères, near Paris. They are sharing one support car, which carries their food and spare clothing, so they need to ride the entire 750 miles together. Their average age is about 30 but their voice of experience, Bernard le Strat, is 50.

Bernard Le Strat (left) and Michel Poisson on Roc'h Trevezel

(Source: David Fisk)

"Team Acheres," as I call them, allows disbandment under one condition: on steep hills each rides his own pace, and they regroup at the top. On a climb called Roc Trevezel, Dominique goes off the front. Poor judgement and youthful enthusiasm take over, I chase him, and we leapfrog to the top. "Heck, only 400 miles left, why not pick up the pace?"

Brest--375 miles--half way! But I am not thrilled. It’s the only checkpoint without a decent "self." Bernard buys me a chocolate protein drink and I use it to wash down the last of my two-day old Camembert sandwiches. Fortunately, Camembert can’t decompose much more than it already has in becoming Camembert; the food goes into the furnace like all the rest, but I wish I had more.

I have just completed 600 kilometers, a distance equal to but hillier than my longest qualifier, and I am about as tired now as I was then. Doing it all again is an entirely new concept. I don’t know how easy it is to catch a train from Brest to Paris, so I simply turn the bike around and get on.

But riding through a sunny afternoon with my new friends we talk about anything in our abilities to speak and understand the other's language. During supper at the Carhaix-Plouguer checkpoint we are joined by four others looking for night riding company: Canadian Hans Breuker, and three Americans, one from St. Louis (whose name is lost in the fog of sleep deprivation), and Steve Bales and Hubert Hawley, two amiable, if uncharacteristically small, Texans. As we roll out of town, the second night of PBP '83 engulfs us, and my few remaining interactive brain cells rummage for tricks for staying awake. I reflect on Charles Bowden's inspiring story of the 1982 Arizona Bicycle Challenge but I’m no longer inspired. I consider, as he did, that my bike’s chain contains 500 parts working in harmony and wish that my mind and body had such harmony. What ultimately keeps me going is the memory of my stateside sendoff party. I sense that all those cycling friends, and Mom and Dad, are all beaming energy across the pond to me. Now I'm riding for them, and for the honor of the ‘Greasy Gonzos’ club T shirt I wear.

Here I am, 3000 miles from Vermont, riding through rural France, in the dark, with ten strangers, devouring caffeine candies, wondering what gear I'm really in. How do you know at night, when you can’t see the slope of the road, you haven’t slept nearly enough, and your sense of speed is screwed? The magnitude of this event hasn't quite penetrated my skull to lend its inspiration. For the moment, enduring has priority. But somehow I know that the images of these few days are being etched in memory, so different is this ride from any other. I have never seen such a complex but precisely orchestrated cycling event.

Around midnight we begin our exchange of French and English songs. But fatigue is a powerful adversary. Hans falls asleep momentarily on his bike and admits when he wakes that it frightened him. It would have frightened me, too, to see a sleeping rider just a foot to my right.

Ten of our group decide to sleep at Loudeac, the place with the beds, still 285 miles from Paris. I calculate that by riding through the night I can finish in less than sixty hours, quite a respectable time, and I wouldn’t have to ride through a third night. Several iterations of the arithmetic support this theory, so when the others head for the sack, I stop only long enough for a meal.

Back in the countryside, I focus on distant taillights and pick up the pace to elevate my heart rate. Two Frenchmen detect a good draft and fall in behind. I speed up again to catch some more red lights and the Frenchmen wonder what I'm doing, one saying to the other "Capricieux." Foolish. And perhaps true.

Approaching the town of Quedillac in the wee hours, the night is suddenly ablaze when the floodlights of the second secret checkpoint switch on. The break destroys my concentration, so I munch half a dozen caffeine candies for motivation. No effect. Back on the bike, I commit the error of reviewing my previous calculations, and discover that my sixty hour finish requires a 20 mph average for the remaining 250 miles. This is not good because I have never been mistaken for the Irish classics champion Sean Kelly. Demoralized, I coast the two miles down to the Quedillac checkpoint, where mattresses are spread on a gymnasium floor. I ask the monitor not to wake me until 6 p.m. He suggests that, perhaps, 6 a.m. is more appropriate. "Oui, merci," I say. 6 a.m. is only three hours away.

6 a.m. wake-up call. But the chef isn't up yet so omelettes aren't on the menu. Nothing else is inviting. I need about 15,000 calories a day for this ride, so I just I eat something not very memorable.

I've been wearing my second and last jersey for 24 hours now but no one seems to mind. I splash some water on my face and walk stiffly out to my bike. Some eight or nine year old kids ask, "C'est dur?" Is it hard? I really don't know if they're talking about the ride or the saddle. I say, "Oui, c'est dur." I think: “When was a group of American kids ever curious or awake enough to ask at 6 a.m. how my ride was going?”

I'm wearing my cycling shorts two at a time now to keep myself as far from the seat as possible. It hurts most during the transition between sitting and standing so I remain in one position as long as possible. But O The Joy Of Cycling! Half an hour down the road, as the sun warms the air, I begin to feel better. Next stop, Tinténiac.

Day 3

Bernard and Team Acheres rise early in Loudéac and passme while I sleep. They’re leaving the Tinténiac checkpoint as I arrive. Bernard guesses what has happened to me and asks with a wry smile why I'm not yet in Paris. I sign another autograph book but this time Haldeman's name is probably three pages ahead of mine. In Tinténiac’s self I get steak and green beans. Fuel in the furnace and I'm ready to roll.

I ride with Team Achères much of the day, but it’s mostly a blur. I get hungry and tell Bernard I’m going to peel off to go grocery shopping. Bernard objects, pulls a can of rice pudding from his handlebar bag and hands me a spoon. He holds the can and I eat, riding alongside. We make it to the next checkpoint and share a meal there.

Riding into the third night I'm still amazed--spectators are hanging out second story windows at midnight, cheering. I hear that an American's shoe fell apart, and a checkpoint official insisted they wake a cobbler to make the repair.

American Ed Sibert's high school French pays off when he recalls that the one food that you can get any time, anywhere in France is "croque-monsieur"--a grilled ham and cheese sandwich. Ed has no problem locating pastry shops, either. At one point, tired of drinking Coca-Cola from tiny 5-oz. bottles, he marches into a bar, sits down and orders a liter. Another patron, not aware that  Americans are generally weaned on the stuff, bets him the cost of the bottle he can't drink it in one sitting. Running on "croque-monsieur," French pastry, and free Coke, Ed will complete PBP in the time of 65 1/2 hours, a top-15-percent finish. Not bad for PBP’s youngest rider--age 17. Americans are generally weaned on the stuff, bets him the cost of the bottle he can't drink it in one sitting. Running on "croque-monsieur," French pastry, and free Coke, Ed will complete PBP in the time of 65 1/2 hours, a top-15-percent finish. Not bad for PBP’s youngest rider--age 17.

2 a.m. In Bellême, we split up, Team Acheres to meet their support car and beds, me to find a meal. In the Bellême checkpoint-slash-restaurant's bathroom I find the first bar of soap I've seen in three days and wash everything decorum allows. Barely able to operate a fork, I almost fall asleep on a reasonably good steak. I’ve heard that the riders' lodging in this town slept in a cold hayloft, and the restaurant's padded chairs beckon. I stretch out on four of them and sleep soundly for three hours. I hear the waiters discussing “le grand Américain,” (I have a flag sewn onto one sleeve) but they don’t disturb me.

7 a.m.: I leave Belleme, again in the company of Team Acheres, who spent an uncomfortable night in the straw. I do much of the pulling; 95 miles left and I can smell the barn. But Jean-Francois has a painful knee, and for his sake Bernard reins me in. We lower Jean-Francois's saddle a half inch, which eases the pain, but I'm still champing at the bit. After 83 miles together, the group breaks up on the long climb out of Beynes, which Bernard and I take together. When he slows at the top to wait for the others, I tell him I feel obliged to finish in a sweat. So I leave them and cover the remaining 17 miles in 50 minutes. I'm pleased but my left Achilles tendon is not.

In the uphill kilometer to the finish (of course: this is France) I sneak by another American, Jim Rex, who during the 1956 revolution escaped Hungary on a bike with a fresh bullet hole in his leg. Jim winds up an impressive spin and pulls alongside. One minute later the whole thing is over: 82 hours, 55 minutes. We're 38 hours behind the first finisher, and 92 years, 11 1/2 hours behind Charles Terront and his balloon-tired one-speed. The magnitude of completing Paris Brest Paris will not hit me for months, but will stay with me for years. Jim tells me that when I get my act together I'll be a really good rider. Get my act together? 83 hours is just fine with me.

FIN

|