|

First official audax ride in France, April 1904

The Union

Des Audax Francais: An Abridged History

by Ken Dobb, based

on the book by Bernard Deon

I. Introduction

Randonneur cycling is an offshoot of an

older form of long distance cycling, something that might be

termed "Audax-style" cycling. Audax-style cycling is

long distance cycling in a single peloton - frequently organized

into a double pace line - at a moderate constant speed and under

the supervision of a ride captain. As is the case with randonneur

cycling, events take place on predetermined routes of fixed distances.

However, unlike randonneur cycling, Audax cyclists conform to

a predetermined ride schedule that is dictated by the average

speed the ride captain hopes to maintain. Randonneur cyclists,

by contrast, ride at a speed set by themselves. Groups are formed

as a matter of convenience, temporary alliances made on the road

with those of a similar fitness level.

In other respects, Audax cycling is very

similar to the randonneur model. Audax cyclists participate in

brevet rides, a brevet series comprising events of 200, 300,

400, and 600 kilometers. Just as the highest attainment of a

randonneur cyclist is the award of the Super Randonneur 5000

medal, so Audax cyclists strive to attain the Aigle d'Or which

has similar, though not identical, qualification requirements.

Among these requirements is the completion of Paris-Brest-Paris.

An Audax version of this event is held every five years, 2006

being the most recent edition. [note: a PBP Audax was held in 2011.]

Paradoxically, though randonneur cycling

is a derivative of the older Audax model, it is the newer style

of cycling that has retained control of the original organizational

expression of French long distance cycling - the Audax Club Parisien.

Audax cyclists, consequently, trace their origins not to the

founding of that club, but to the organization of the first Audax

brevet in France. This took place in Paris in April 1904. The

year 2004 thus marked the centenary year of the organization

of these events. To honour the occasion, M. Bernard Deon authored

a magisterial history of Audax cycling. His work, "Un Siecle

De Brevets d'Audax Cycliste" (self published, 2006), forms

the entire basis for what is written below: the following article

should be seen as a rough abridgement of M. Deon's finely detailed

research.

II. Origins And Early Years: 1904 -

1920

1. Cycle Tourism In France At The Commencement

Of The Twentieth Century

According to M. Deon, the origins of Audax

cycling can be attributed to the dissatisfaction of Henri Desgrange

with the state of cycle tourism in France at the  beginning of

the twentieth century. Since the 1890's, cycle tourism in France

had come under the sway of the Touring Club de France. This organization

was an affiliation of individual touring cyclists. These cyclists

belonged largely to hundreds of local clubs that, for the most

part, organized what might be termed "social cycling"

events, rides of short distances and an unchallenging nature,

ridden purely for pleasure. beginning of

the twentieth century. Since the 1890's, cycle tourism in France

had come under the sway of the Touring Club de France. This organization

was an affiliation of individual touring cyclists. These cyclists

belonged largely to hundreds of local clubs that, for the most

part, organized what might be termed "social cycling"

events, rides of short distances and an unchallenging nature,

ridden purely for pleasure.

At one point, all amateur cycling in France

had been organized under the auspices of the Union Velocipedique

de France. Since the emergence of the Touring Club, the interest

of the U.V.F. in cycle tourism had all but disappeared. A brevet

ride of 500 kilometers over five days was on the U.V.F. books,

but had fallen into disuse. Similarly, brevets of 50, 100, and

150 kilometers, originally designed as inducements for cycle

tourists, had turned into competitive time trials for racers.

What Desgrange was looking for was a way to revive these non-competitive

events, for a form of cycling that would prompt ordinary cyclists

to perform impressive feats of endurance.

Desgrange was, himself, a cyclist of repute.

Upon completion of his competitive cycling career he had been

recruited to assume the direction of the daily sport newspaper

L'Auto-Velo (shortly to become, simply, L'Auto), Under his direction,

this journal originated and assumed organizational responsibilities

for the Tour De France and became a powerful influence through

the breadth of French organized sport.

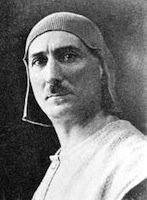

Vito Pardo and Audax Italiano, 1904

2. Audax Italiano

Desgrange found the style of cycling he

was searching for in the events organized by Audax Italiano.

In June of 1897, twelve Italian cyclists

left Rome for Naples to determine whether they could complete

the 231 kilometer distance in the daylight hours of a single

day. Nine riders finished the distance becoming the first group

of civilian long distance cyclists to complete a ride in the

Audax style. Some time later, a group of Neapolitan cyclists

performed the same feat in the reverse direction. At the banquet

celebrating the accomplishment of the twenty riders who had completed

the return journey successfully, the idea of creating an organization

of cyclists interested in riding distances of over 200 kilometers

was ventured. style. Some time later, a group of Neapolitan cyclists

performed the same feat in the reverse direction. At the banquet

celebrating the accomplishment of the twenty riders who had completed

the return journey successfully, the idea of creating an organization

of cyclists interested in riding distances of over 200 kilometers

was ventured.

At a meeting in Rome in January, 1898,

cyclists from all over Italy assembled and brought into being

Audax Italiano. Vito Pardo, who had captained the original ride

of the Roman cyclists to Naples, was elected President. Pardo,

an amateur sculptor, designed the original medal and diploma

that were awarded to each Italian cyclist who had completed an

organized 200 kilometer ride. By the end of 1898, Audax Italiano

was comprised of 12 sections and counted 244 cyclists as members.

By 1902, 1938 member cyclists were organized in 81 sections.

The organization continued its growth in the years before the

First World War, peaking at 7077 members in 214 sections in 1913.

A tradition of exchanging visits among

cyclists of different cities developed. In 1900, for instance,

Milanese cyclists organized four official rides of 200 kilometers.

In the same year, they traveled in groups to visit their counterparts

in Rome, Pisa, Monza and Lugano in Switzerland. Other members

of Audax Italiano ventured across the border into France, interesting

French cyclists - particularly those in Nice - in their activities.

3. 1904: The First French Brevets

Through 1901 and early 1902, Desgrange

ruminated in the pages of L'Auto-Velo on the state of cycle tourism

in France. In an editorial in August 1902, however, he advanced

an idea of cycle tourism based on groups led by ride captains

at a fixed moderate pace over distances of 150 to 200 kilometers.

Clearly, Desgrange was describing the cycling practiced by the

riders of Audax Italiano. At about this time, L'Auto-Velo began

to publish in its pages, without comment, announcements of the

planned ride programmes of the Italian organization.

In late 1903, L'Auto-Velo (or L'Auto as

it had now become) announced a planned excursion of the Turin

section of Audax Italiano to Paris in the following year. This

journey of 760 kilometers was projected to be completed over

four days. L'Auto undertook to arrange a reception of the Italian

cyclists on the road to Paris. At the same time, the journal

suggested that French cyclists organize themselves to conduct

long distance cycling on the Italian model.

In January 1904, Desgrange announced the

creation of a society of Audax cyclists in France. A first event

was planned for Easter Monday, April 3rd on a route between Paris

and Gaillon. Gaillon was located on the classic route between

Paris and Rouen that had been the course of the first inter-city

velocipede race in 1869. The village is the site of a particularly

difficult hill climb, chosen for this event as a test of the

mettle of the first participants of the new form of cycling.

Paris - Gaillon was to become a classic route for French Audax

cyclists, re-ridden on numerous occasions.

Four preparatory rides of progressively

increasing distances were held in anticipation of the April event.

These rides were all captained by Charles Stourm, a former racing

cyclist closely affiliated  with L'Auto. In March, subscriptions

for the April event - limited to fifty places - were offered

at the offices of the newspaper. The places were all filled within

seven hours, with an additional fifty applicants turned away. with L'Auto. In March, subscriptions

for the April event - limited to fifty places - were offered

at the offices of the newspaper. The places were all filled within

seven hours, with an additional fifty applicants turned away.

On April 3rd, 37 cyclists gathered at the

Port Maillot in Paris at 3 a.m. Again under the leadership of

Stourm, the thirty finishers covered the 200 kilometer distance

in 16 hours. Discounting the 2 1/2 hour lunch stop in the town

of Vernon, their average speed was 15 kilometers an hour. The

finishers were the first to be accorded the status of Audax cyclists,

a designation that was reserved for those cyclists that had completed

an official ride of 200 kilometers. Each Audax designee was awarded

a diploma and a medal of yellow enamel by L'Auto, on which was

inscribed the unique number, in chronological order, assigned

to each Audax designee. Charles Stourm was awarded the accolade

of being designated Audax #1.

By the end of 1904, a further nine official

200 kilometer rides had been organized and successfully completed

in Paris. An additional 20 rides of 200 kilometers had been completed

in twelve other French cities. At year-end, 1018 cyclists had

been awarded the Audax designation. A highlight of the year was

the reception of 100 or so members of the Turin section of Audax

Italiano who had cycled to Paris in mid-July. Timed to coincide

with this event, a group of newly-designated Audax riders from

Lyons paid a return visit to Turin.

4. Formation of the Audax Club Parisien

On November 30, 1904, a meeting of interested

cyclists who had received the Audax designation met in a Parisian

cafe. The meeting was held on the initiative of Armand Le Rendu

(Audax #261) who was elected President of the newly formed club

- the Audax Club Parisien. The club was to be comprised exclusively

of those men who had received the Audax designation. Women who

had achieved the Audax designation were permitted honorary membership,

receiving the right to be full members only in 1912. Among the

sixteen founding members was Charles Stourm, adding by his presence

a certain gravitas to the new organization. Of significance for

the future of the organization, a proposal to add the word "Cycliste"

to the title of the association was rejected.

5. Development of a Cycling Programme

In the first years, official Audax brevet

rides were organized and conducted by cyclists affiliated with

L'Auto. This was equally true in the cities outside Paris, where

the newspaper's local correspondents took the task of organization

upon themselves. However, by 1906 this organizational responsibility

had been conferred on the A.C.P, with L'Auto acting solely in

the capacity of validating ride results. Beginning in 1907, the

official 200 kilometer rides began to be referred to as "brevet"

rides, the word "brevet" referring to the diploma that

was awarded to those who had completed the ride.

Between five and seven brevet rides of

200 kilometers were organized in Paris each year. This practice

continued even through the cycling seasons effected by the First

World War, those of 1915 through 1918. Equally, brevet rides

continued in a number of French provincial cities. The result

of this sustained activity was a steady growth in the numbers

of Audax cyclists - 2000 by August, 1907; 2741 by the end of

the 1909 season; more than 3500 at season end 1911; 4600 in April

1914 (the tenth anniversary of the initial 200 kilometer ride);

and 6000 by July 1918.

Almost immediately upon completion of the

first 200 kilometer rides, Audax cyclists sought to complete

longer distances. On May 28, 1905, the first 300 kilometer ride

- an event termed a "raid" in French - was attempted

by 11 members of the A.C.P. Ten riders finished the 316 kilometer

route in 22 hours and 30 minutes. In June 1908, 3 riders from

the Honfleur section in Northern France completed the first official

ride of 400 kilometers. The first Parisian 400 was completed

one month later by 20 cyclists in 23 hours, 30 minutes.

The A.C.P. scheduled one 300 kilometer

event and one 400 kilometer event from Paris each year, a practice

that was emulated by a number of the provincial sections. A rider

who successfully completed these rides was awarded a star to

add to the yellow enamel medal presented to Audax designees,

blue for completing a 300 kilometer ride, red for a completed

400 kilometer ride. Desgrange was sceptical of these newer distance

rides, considering them to be "a bit too long". While

he was willing to homologate the results of the 300 and 400 km

events, he declined to consider them as official Audax events,

leaving the organization and conduct of these events to the A.C.P.

The practice of cycle tourist excursions,

begun in Italy, was continued in the annual A.C.P. ride programme.

Periodic club excursions to a number of destinations in France

were scheduled throughout the pre-war years.

6. A Non-Cycling Audax Programme

Again in 1904, several months after the

first official 200 kilometer ride, the first official event of

Audax Pedestres was held under the auspices of L'Auto. The event

was modeled on its cycling counterpart. The event distance -

fixed by Desgrange at 100 kilometers, a distance decried as monstrous

by his contemporaries - was to be essayed under the control of

route captains. At the end of the two day walk, 64 successful

hikers received a diploma and a blue enamel medal to mark their

achievement and their designation as an Audax hiker. Through

time, a programme of official walks was established, with the

hikers elaborating their programme to include hikes of longer

distances - 130 and 150 kilometers. In August, 1905, a competing

organization of Audax designees was created - the Audax Club

de France. The goal of this organization was to group Audax cyclists

and hikers in one club. An event programme accommodating both

groups was established, but quickly the cyclists defected to

the A.C.P. The Audax Club de France became an organization exclusively

of hikers, to which, in time, Desgrange extended the responsibility

of organizing hiking brevets.

In 1913, A further Audax discipline was

added - swimming. In June of that year 10 swimmers entered the

Marne on the western periphery of Paris. They were attempting

to complete a distance of six kilometers within a three hour

time allowance. Among the seven finishers was Henri Desgrange

himself. Desgrange had already completed the required hiking

distance, and in 1912 had ridden his first 200 kilometer cycling

event. With the completion of the swim, he became the first person

to receive the Audax designation in each of the three disciplines

then extant.

A fourth discipline - rowing - was added

in 1921. The first brevet event of eighty kilometers, within

a time allowance of twelve hours, was held in September. Again,

Desgrange was among the sixteen participants who completed the

event. He chose, however, to downplay his participation. The

spotlight was instead shone on the accomplishments of Raphael

Boutin, who had now finished all eight Audax events (the three

cycling, three hiking, as well as the swimming and rowing brevets),

and who had, earlier in the year, assumed leadership of a new

organization of Audax cyclists.

III. Organizational Wars: 1913 - 1931

1. Introduction

Desgrange can be thought of as having three

design principles in mind in the creation of the Audax movement.

His aim, at the outset, was that the Audax movement be multi

disciplinary, embracing not simply cycling, but other sports

as well. Similarly, his intent was that the sports each be a

means to foster physical well being rather than a setting for

individual performance. In cycling, this meant wedding the pre-existing

brevet event structure to the disciplined group riding style

we now term "Audax". Third, he was a partisan of the

Union Velocipedique de France and believed that this organization

should be the sole organizing body for French cyclists. He opposed

the claims of the rival Touring Club de France to represent separately

the interests of touring cyclists.

Each of these three principles was subject

to a challenge by the cyclists organized under the rubric of

Audax cycling in the years just prior to, and following, the

First World War. This led to three organizational crises that

upset and split the Audax movement. Among other things, this

conflict led to the formal beginnings of randonneur cycling.

2. Schism 1913

The initial organizers of the Audax Club

Parisien intended that membership in the club be reserved for

those who had successfully ridden the 200 km official brevet

ride and had thus earned the Audax designation. In 1910, with

the resignation of Le Rendu as club president, this membership

rule was relaxed. The immediate consequence was an influx of

new members who were interested less in long distance cycling,

than in hiking and in shorter distance cycling excursions. Hiking

trips were initially introduced for the winter months. They proved

an immediate success. An initiative in 1912 to extend the hiking

programme to the summer months led to a harsh reaction from those

club members dedicated to distance cycling.

The club broke into two factions with quite

different views of the club's future. A working group attempted

without success to reconcile the differences between the contending

groups. At the January 1913 general meeting, two resolutions

expressing the opposing viewpoints were placed before the membership.

The resolution favoured by the long distance cyclists lost. The

majority group, those that favoured combining hiking activities

with cycling, by and large were uninterested in the Audax designation.

After some wrangling, the representatives of the majority group

decided to leave the organization of the Audax Club Parisien

in the hands of those club members who had a continuing interest

in the Audax designation and in participating in the club's long

distance rides. The members of the majority faction left to form

a new club, Les Francs Routiers. Their departure reduced membership

in the A.C.P. by about two-thirds. It also confirmed the mandate

of the club as committed to the promotion of the single sport

of long distance cycling.

For his part, Desgrange expressed no opinion

on this rupture save to reaffirm the role of the A.C.P. as the

organizer of official Audax brevet rides. Audax France continued

in its role of organizing the official Audax walking events.

3. Rupture 1921: The Beginnings of Randonneur

Cycling

Those who had led the response to the proposals

of the hiking group on behalf of the long distance cyclists would

be those who came to play an important part in the conversion

of the A.C.P. to the randonneur style of long distance cycling.

Among these was Louis Roudaire. Roudaire had been an editor at

L'Auto under Desgrange. His pronounced interest in bicycle tourism

led him to found his own journal in 1910 - Le Cyclotouriste.

It led him, as well, to a close association with the cycle tourist

movement known as the Ecole Stephanoise and with its spiritual

leader, Paul De Vivie.

The Ecole Stephanoise was an informal grouping

of touring cyclists who lived and worked largely in the St. Etienne

/ Lyon area of southeastern France. Participants in this grouping

were passionate advocates of the improvement of cycling technology.

Several made important design contributions to the advancement

of multi-gearing. The development of the derailleur, in particular,

benefited from the technical innovation of cyclists from this

group. Through his editorial contributions to his newspaper,

Le Cycliste, De Vivie played a key role in propagating interest

in bicycle technology, and in bicycle tourism more generally.

Le Cycliste also fostered the cycle tourist movement through

the promotion of periodic regional gatherings of its readers

at which technical developments were discussed.

Members of the Ecole Stephanoise practiced

a form of long distance cycling that was rooted in traditions

other than that of the disciplined group cycling that originated

with Audax Italiano. Increasingly after 1901, rides emphasising

cyclist performance were reported in the pages of Le Cycliste.

Among these were the annual rides undertaken each Easter by De

Vivie and his colleagues, from his home in St. Etienne over several

hundred kilometers to a predetermined destination in Provence.

These long distance rides presented an alternative model of long

distance cycling for key members of the A.C.P.

It was Roudaire who suggested the first

formal contact between the two groups. An initial meeting between

De Vivie, the A.C.P. and several provincial sections of Audax

riders was held at Nevers in 1908. Subsequently, Le Cycliste

organized annual regional meetings of riders from several Paris-area

cycling clubs at which members of the A.C.P. figured prominently.

After the 1913 rupture, the influence of

De Vivie's movement in the affairs of the A.C.P. became more

pronounced. Immediately after the announcement of the withdrawal

of the hiking members of the club, Roudaire, now named honorary

president of the club, announced that his newspaper would sponsor

a "polymultipliee". This was a sort of test of touring

bicycles or, more specifically, competing systems of multiple

gearing. The competition, held over a hilly course, was designed

to foster competition among bike and component manufacturers.

The A.C.P. provided material support both to this event and to

a second multiple gearing "championship" that was held

before the outbreak of the First World War.

Equally significantly, Roudaire introduced

changes in the Audax riding style. Under his presidency in 1910,

the club had introduced the use of control cards. Until this

point, the ride captain had held a roll call at each control

point along a brevet route, disqualifying those riders not present

for his call. It had been found, however, that some riders who

had been dropped by the main peloton, for one reason or another,

nevertheless reached the control within the official time limit.

The control card was introduced to enable these riders to record

their arrival time and to continue their ride.

Roudaire now took this a step further,

introducing control opening and closing times based on a 25 kph

maximum and an 15 kph minimum speed. This innovation, introduced

for the running of the 300 and 400 km brevets in 1913, marks

the unofficial beginnings of randonneur cycling. the club executive

was quite conscious of the change that was being made. The ride

regulations for that year contain the following comments:

"As much as it is easy to complete

in a peloton an outing of 200 kilometers under the direction

of a ride captain, it becomes difficult to hold together cyclists

over 300 kilometers, and still more difficult over 400 kilometers.

Competitors [sic] will manage their progress according to their

fitness, always provided that they take aim at the control opening

and closing times, arriving neither before nor after. As it is

advantageous to ride together in groups, rather than as isolated

cyclists, the competitors [sic] may form one or more pelotons

as they wish."

This is a marked departure from the formula

of a single group riding at a moderate speed under the control

of a ride captain that had been the norm for official Audax rides

up until this point. To further underline the departure, the

club executive announced that medals would be awarded to those

club riders who could establish new record times at each of the

300 km and 400 km distances.

The intervention of the First World War

led to a suspension of any discussion within the club that this

change might have provoked. A programme of official rides was

maintained on roads away from the war sector throughout the duration

of the conflict, despite the departure of much of the club leadership

for active duty. However, upon cessation of the hostilities,

the changes introduced by the Roudaire-led club executive became

a matter of controversy. Desgrange began not to publish announcements

of forthcoming rides of 300 and 400 kilometers that employed

the formula of opening and closing control times. A confrontation

between and Desgrange and the A.C.P. over this matter resulted

in the resignation of a member of the club executive in 1920.

Things came to a head in 1921. Some members

of the club were now advocating that the formula of opening and

closing control times be applied to 200 km brevet rides as well.

During the first official 200 km brevet ride of the season, on

April 10th, the ride captains set a very quick pace that soon

split the peloton. Many of those left behind regrouped behind

an impromptu ride leadership and finished the brevet at a moderate

pace. Subsequent to this event, Desgrange published a brief statement

in the pages of L'Auto withdrawing the responsibility for organizing

official Audax rides from the A.C.P. and once again conferring

this responsibility on his newspaper. A subsequent brevet ride

on April 22nd was held under the leadership of ride captains

of Desgrange's choice. Needless to say, Audax ride conventions

were observed during this event.

The withdrawal of the right to organize

Audax events left the leadership of the A.C.P. in a quandary.

After a period of some recriminations, the club regrouped and

announced the introduction of the "Brevets des Randonneurs

Francais". The first brevet ride under this rubric was a

200 kilometer event held on September 11, 1921.

There can be no doubt that other matters

contributed to this rupture. In the immediate aftermath of the

War the leadership of the T.C.F. proposed that a polymultipliee

event be held in the near future. As Roudaire's cycling journal

had disappeared during the war years, another sports journal,

a direct competitor of Desgrange's paper, took the task of promoting

this event upon itself. Again, the A.C.P. signed on to support

this event, but where A.C.P. participation in the past had not

provoked Desgrange's interest, club support of the 1921 event

prompted bitter recriminations. This matter, however, simply

added fuel to a fire that was already burning. The controversy

over the appropriate manner of conduct on official rides had

already created deep divisions among members of the club.

4. The Creation and Alignment of The Union

Des Audax Cyclistes Parisiens

The figure that emerged as the leader of

those disaffected with the randonneur riding style was the rather

corpulent one of Raphael Boutin. Too old for active service in

the war, Boutin had joined the A.C.P. during the 1914 season.

He had quickly accumulated the medals for the three official

Audax rides, and soon had become pressed into service as a ride

captain. He had lost this position in the  aftermath of the war's

end, but the experience stood him in good stead. It was Boutin

who had rallied those riders left behind by the ride captains

of the first brevet of the 1921 season, and it was to Boutin

to whom Desgrange turned to lead those riders who participated

in the brevet of April 22nd, the first organized without A.C.P.

participation. aftermath of the war's

end, but the experience stood him in good stead. It was Boutin

who had rallied those riders left behind by the ride captains

of the first brevet of the 1921 season, and it was to Boutin

to whom Desgrange turned to lead those riders who participated

in the brevet of April 22nd, the first organized without A.C.P.

participation.

Boutin took on the task of creating a new

club to carry on the organization of Audax brevets at Desgrange's

suggestion. As has been noted above, Boutin was among the first

to have received all the Audax awards in each of the four Audax

disciplines. His impulse was to create the new club along multi-disciplinary

lines. However, his overtures to the hiking organization - Audax

France - were not well received, with the consequence that Boutin's

new club became one exclusively for cyclists. The Union Des Audax

Cyclistes Parisiens was created in April, 1922.

The rupture proved to be far less calamitous

for the membership numbers of the A.C.P. than the earlier schism

of 1913. At an early founding meeting of the Union des Audax,

only four of the eleven members present had been members of the

A.C.P., the remainder largely being newly qualified Audax designees.

Members of each club began participating in the rides of the

other. Boutin himself went out of his way to avoid stirring enmity

between the two organizations. Among his conciliatory moves was

ensuring the membership of the Union des Audax in the federation

of bicycle touring clubs newly created by his harshest critic

in the A.C.P., Gaston Clement.

Clement had been a ride captain in the

first decade of the A.C.P. He had served on the A.C.P. executive,

and had been among the leaders of the club who had opposed the

diversification of the club into a hiking programme in 1913.

By 1920, Clement had become a member of the steering group of

the Touring Club de France. This organization, founded initially

by bicycle tourists, had changed in character through the years.

Especially after the advent of the automobile as a reliable mode

of transportation, the club had become more focused on purely

touring matters. The interests of bicycle tourists were increasingly

set aside in favour of the interests of tourists of more affluent

means. Clement worked within the T.C.F. to counter these trends.

Stepping into the shoes of Roudaire, it

was on Clement's initiative that the first post-war polymultipliee

had been organized under T.C.F. auspices . This event, held at

Chanteloup, became an annual fixture in the French cycling calendar

for many years. He took the idea of this event a step further

by organizing the first editions of a cycling week of friendly

competition for touring cyclists. The Semaine D'Auvergne held

in July 1922 was a test of 700 kilometers over five stages through

mountainous terrain. A second event in the Dauphinee region was

held in the subsequent year. A cycling week - La Semaine Federale

- has become an annual tradition for cycletourists in France. He took the idea of this event a step further

by organizing the first editions of a cycling week of friendly

competition for touring cyclists. The Semaine D'Auvergne held

in July 1922 was a test of 700 kilometers over five stages through

mountainous terrain. A second event in the Dauphinee region was

held in the subsequent year. A cycling week - La Semaine Federale

- has become an annual tradition for cycletourists in France.

In early December,1923, Clement hastily

called a meeting to create a new federation of bicycle tourist

clubs under the auspices of the T.C.F. Representatives of five

cycling clubs from the Paris area agreed to join together to

form the new organisation. Of the seventeen persons present,

eight were affiliated with the A.C.P. The Federation Francaise

des Societes de Cyclotourisme was officially brought into being

several days later. The U.A.C.P. was one of fifteen clubs represented

at the first F.F.S.C. general meeting in February, 1924. Clement

was elected president of the Federation, while Boutin was elected

as a member of the executive committee.

Clement's initiative was probably prompted

to head off some behind the scenes manoeuvring between the executives

of the T.C.F. and the U.V.F. Despite Clement's efforts, an accord

between the two organisations was announced in April 1926 that

gave effective control of cycle touring events to the U.V.F.

These events were to be placed in the hands of a cycle tourist

commission, the membership of which was to be selected by the

U.V.F. While clearly under the control of the U.V.F., the commission

was nominally part of the T.C.F. Some part of the intent of this

accord was clearly to drive the F.F.S.C. out of existence. Participation

in events sanctioned by the cycle touring commission of the T.C.F.

was open only to members of the U.V.F. or members of clubs and

societies associated with the U.V.F. Clubs affiliated with the

F.F.S.C. were required to drop that affiliation if the events

that they organized were to receive T.C.F. authorisation.

This accord seems to have had little immediate

effect on the U.A.C.P. In 1928, at the ceremony conferring the

10,000th Audax designation on the popular French racing cyclist

Eugene Christophe, the president of the F.F.S.C. was present,

as was Gaston Clement.

In 1930, however, Desgrange again withdrew

the right to organize Audax brevets from the club to which he

had previously entrusted the task. He now conferred that responsibility

on th U.V.F. The U.V.F. would not itself organize Audax brevets,

but would delegate this task on a regional basis to applicant

clubs. The U.C.A.P. was thus placed in a position where it felt

compelled to apply to the U.V.F. in order to continue its established

ride programme in the Parisian region. The U.C.A.P. eventually

took this step, but not without first exploring other options.

Among the casualties of this upset was the promising young president

of the club - Andre Griffe. Griffe appears to have made a deal

with Desgrange supporting the initiative, without the knowledge

or support of the club executive. The upset caused by Desgrange's

manoeuvre led to Griffe's resignation from the club. At the same

time, the club's membership in the F.F.S.C. was revoked.

In the ongoing struggle over the representation

of the interests of bicycle tourists, Desgrange was able to reassert

his belief that the interests of French cyclists were best served

through membership in a single organization - the U.V.F. As had

been the case with the style of riding adopted during the course

of Audax events, Desgrange had used his authority to reaffirm

the principles that had guided his initial creation of the Audax

movement.

IV. An Audax Ride Programme: Advance

and Recession 1921 - 1945

1. Reaffirming The Audax Cycling Style

The pre-war initiatives of the randonneur

cyclists in the A.C.P. had placed in doubt that the 300 and 400

kilometer events could be cycled in the customary Audax style.

Raphael Boutin saw as among the most important tasks he faced

in the direction of the new organization of Audax cyclists, the

re-establishment of these rides in the Audax ride programme.

An initial 300 km event was completed in 21 hours on June 18,

1921. Fifty-nine of the sixty-one cyclists who started the event

managed to finish, riding the moderate, controlled pace of the

Audax style. Similarly, twenty-one of forty-one starters finished

the 400 km ride held on July 23, 1921, again riding in the Audax

style.

Desgrange, who until this point had considered

these distances to be too long, conferred official brevet status

on these events for the first time. However, he refused an application

by the club to participate in Bordeaux - Paris, a race at that

time organized by his newspaper. This race, the oldest in the

professional race calendar, had been the object of attention

by Audax riders for some years. From the outset of the event,

amateur participation had been permitted in an event held in

parallel with the professional race. The proposal to Desgrange

was that an Audax ride be organized on the race route and run

in conjunction with the race. For his part, Desgrange wanted

to rigorously separate Audax cycling from any association with

racing.

This refusal left Boutin with a desire

to push the boundaries of Audax cycling. He looked to establish

an event of 600 kilometers, roughly the distance of Bordeaux

- Paris. He scouted the route, Paris - Dijon and return, that

was to become the standard 600 kilometer route for the club for

many years. Gaining Desgrange's reluctant agreement, Boutin organized

the first attempt at the 600 kilometer distance on August 5,

1922. Eleven of twelve starters completed the ride, one on a

fixed gear machine, establishing the event as an annual occurrence

in the Audax ride programme.

2. Paris - Brest - Paris 1931

The continuing success of Audax riders

at the 600 kilometer distance led members of the club executive

to look beyond, to the possibility of the participation of Audax

cyclists in Paris - Brest - Paris. This event, begun in 1891,

was considered to be the ultimate marathon challenge for  cyclists.

As was the case for Bordeaux - Paris, amateur participation had

been a feature of the event since its inception and, indeed,

a number of Audax club members had participated in past editions

as individual amateur entrants. cyclists.

As was the case for Bordeaux - Paris, amateur participation had

been a feature of the event since its inception and, indeed,

a number of Audax club members had participated in past editions

as individual amateur entrants.

Among those who looked to Paris - Brest

was Andre Griffe. Griffe had been a member of the U.A.C.P. executive

committee and was elected club president in 1928. In that year,

he opened negotiations with Henri Desgrange to stage a 1000 kilometer

event. Griffe clearly wanted to establish the 1000 km event to

strengthen his case for Audax participation in the 1931 edition

of P.B.P. Characteristically, Desgrange was reluctant. He denied

the 1000 km event any kind of official status. No medals or certificates

were to be awarded. However, he pledged the support of the local

correspondents of L'Auto to man controls along the proposed route.

Forty-two riders started the first 1000

km event on the morning of August 9, 1929. Twenty-five finished

with the main peloton in just under sixty-four hours. An Additional

thirteen finished before the sixty-eight hour time limit. In

light of this success, the club executive decided to make a 1000

km ride an annual event.

The result also strengthened Griffe's hand

in his dealings with Desgrange concerning Audax participation

in P.B.P. Approaching Desgrange after a somewhat less successful

running of the 1000 kilometer Paris - Dijon - Lyon event in 1930,

Griffe was afforded a somewhat more favourable reception by Desgrange.

For Desgrange, Griffe's proposal offered a means for him to rid

himself of the Tourist-Routiers class of riders that had saddled

previous editions of Paris - Brest - Paris with a burdensome

time limit of ten days. The proposed ninety hour limit for Audax

participation offered the possibility of a more streamlined event.

Further, as we have seen above, the proposal offered a means

for Desgrange to corner the young president into agreeing to

support Desgrange's decision to transfer the right to organize

Audax brevets to the U.V.F.

In the event, Audax participation in the

1931 edition of Paris - Brest - Paris turned into a debacle.

The club's proposed finishing time of eighty-five hours committed

them to an average speed of 22 kilometers per hour, somewhat

above the usual average speed then practiced by the club in its

events. It also committed them to just two sleep stops of four

hours each, which they proposed to take on the second and third

nights of the event. The eighty-one Audax starters met strong

head winds and persistent rain showers on the outbound leg, that

both scattered riders on the road and prompted a wave of abandonments.

The commitment to the proposed ambitious time schedule meant

that there was little occasion to round up stragglers who otherwise

might have been reintegrated into the group, and several strong

riders were lost to time limits at intermediate controls making

the attempt. By the time of the first rest stop at kilometer

708, only twelve riders were left in the company of the ride

captains, with several others straggling into the control throughout

the night. Twenty-four Audax riders eventually finished together

at the Velodrome Buffalo in Paris, followed later by five others

who finished within the time limit. It was an inauspicious beginning

to Audax participation in the great event.

3. Regulation, Depression and War

Despite the relative failure, Paris - Brest

- Paris 1931 marked a high water point for the U.A.C.P. The years

that followed saw a contraction of the activities and membership

of the club in the bleak years that concluded only with the cessation

of hostilities in 1945.

The year 1932 saw a marked decline in the

number of new Audax designees, a diminution that was repeated

in the following year. High rates of unemployment among the sectors

of the population from which the U.A.C.P. drew its membership

placed the costs of club membership and the entrance fee into

brevet events beyond the reach of many who might otherwise have

participated. In 1933, only seven cyclists came forward to attempt

the 600 km brevet that year, while the 1000 kilometer event was

canceled for a lack of participants.

The regulatory hand of the Union Velocipedique

Francais was also burdensome. The U.V.F. decreed that it would

recognize only the 200, 300, and 400 kilometer events as official

brevet rides. The U.A.C.P. was permitted to hold 600 and 1000

kilometer events on its own account. However, the club was prohibitted

from using the word Audax - even in identifying the club's own

name - in publicising and commemorating these events. Further,

the brevets of other clubs not affiliated with the U.V.F. were

not permitted to be used as qualifying events for the 600 and

1000 km rides, effectively eliminating randonneur cyclists as

potential participants in the longer U.A.C.P. events.

The U.V.F. went so far as to refuse official

status to the 200 kilometer events known as "nyctocyclades".

These rides had a venerable place in the history of Audax cycling,

originating in the first decade of the century. Audax riders

gathered in Paris in the early evening to ride 200 kilometers

through the night to a seaside resort on the English Channel.

After a day relaxing on the beach, club members would return

to Paris by train, having spent a pleasant weekend away from

the city. The dour officials at the U.V.F. commented that Audax

rides were meant to be conducted, to the greatest extent possible,

in daylight hours.

On the other hand, the national reach of

the cycling federation meant that the Audax formula was more

widely and consistently spread to the regions of France than

it had previously been. While brevet events in the regions experienced

the same contraction as did the U.A.C.P. in Paris during these

years, the concept of a central body responsible for the homologation

of brevet events taking place throughout France, would become

important to the sport's growth in the post-war period.

The club, and Audax cycling generally,

experienced a slow but palpable recovery in the years leading

up to 1939. With the outbreak of war late that year, the club

lost half of its membership to war mobilisation. The onslaught

of invading forces disrupted the 1940 season, and while there

was some effort to resume the club's cycling activities through

the remainder of the war years, a lack of food to sustain riders

on their long rides, and a lack of parts to repair aging bicycles,

meant that the numbers participating in club brevets remained

small. Despite this, there were some glimmerings of optimism

that sustained members through bleak times. A hiking program

that had begun in the Depression found new popularity in the

war years. Further, the club executive created an event for Paris

area cyclists otherwise stifled by wartime conditions. The Etoile

de L'Isle De France was a series of four day trips that took

riders to destinations in the Parisian hinterland in each of

the cardinal directions. Besides the recreational outlet these

rides provided, they formed the basis for co-operation among

cycle tourists from different Paris-area clubs that would become

important in the aftermath of the war.

V. The Post-War Years - 1945 - 1960

1. Aftermath 1945 - 1949

The war was hard on the club, and still

more so on its individual members. The Club's President - Max

Rak - was caught up in the deportations and disappeared. At the

war's end those members who had been prisoners of war in Germany

drifted back, one by one. An oak tree was planted in the forest

at Fontainebleau in their honour, symbolizing hope and new growth.

When the tree died some six or seven years later, it was found

that there were none among the returned P.O.W.s that had retained

their membership in the club to attend the replanting ceremony.

The conflict had positive implications

for the club in other respects. It led, for instance, to a resolution

of the organizational squabbles that had plagued the club during

the thirties. The Union Velocipedique Francais allied itself

with the Petain government and followed that government to Vichy

and, ultimately, obscurity. In its place, in 1941, was created

a new organization, the Federation Francais de Cycle (F.F.C.).

This was followed in the subsequent year by the foundation of

the Federation Francais de Cyclotourisme (F.F.C.T.). These two

organizations remain the principal associations representing

the interests of French cyclists to this day. The club assumed

the duty of the homologation of the results of brevet rides from

the absent U.V.F. and arrogated to itself the right to organize

it own schedule of brevets. This latter liberty was later to

be curtailed as attempts were made to co-ordinate a schedule

of cycle-tourist events in the Paris area through the Ligue Ile-de-France

committee of the F.F.C.T.

Almost immediately in the aftermath of

the Armistice there were efforts to return the ride schedule

to normality. It was only in 1949, however, that the whole suite

of brevet rides, including the 1000 km brevet, was offered by

the club. Similarly, cycling slowly began to return to the French

provinces. Outlying clubs began to submit the results of their

brevet rides to the Paris club.

A further expression of the hunger for

normality was the resurrection of Audax participation in Paris-Brest-Paris.

An attempt was made to revive P.B.P. in 1946, to replace the

edition that should have been held in 1941. This attempt proved

to be premature. A second attempt was made in 1948. The event

was staged in co-operation with organizers from the Audax Club

Parisien, and with the assistance of a small financial subsidy

from the French daily sports newspaper, L'Equipe. L'Equipe was

sponsoring and organizing the professional race with which the

amateur cycling randonnees were being coordinated. It was the

successor to Henri Desgrange's paper L'Auto, that was closed

following the War.

The Audax event was met with similar mixed

success as had been the first, the 1931 edition. Of the 62 starters,

only 42 finished - 39 in the peloton and an additional 3 within

the time limit.

2. Laying the Foundations of the Modern

Club 1950 -1960

Commencing in 1950, the Executive of the

Club began to devote thought and effort to attracting new interest

and participation in the club. A first expression of this concern

was a change in the average speed at which Audax brevets were

conducted. Until this time, 200 kilometer events were usually

ridden at an average speed of 18 kilometers per hour. For distances

above 200 kilometers, an average speed of 20 kilometers per hour

was usually - but not always - applied. After a period of experimentation

with faster speeds, during which there appeared to be no ill

effects on rider completion rates, average speeds of 20 k.p.h

for 200 kilometer brevets and 22.5 k.p.h. for brevets exceeding

200 kilometers were introduced. These average speeds remain the

norm until this day. experimentation

with faster speeds, during which there appeared to be no ill

effects on rider completion rates, average speeds of 20 k.p.h

for 200 kilometer brevets and 22.5 k.p.h. for brevets exceeding

200 kilometers were introduced. These average speeds remain the

norm until this day.

The thinking behind this change was that

higher average speeds would attract younger riders who would

otherwise be attracted by competing cyclo-sportif events. Efforts

were made, as well, to attract and retain strong younger riders

as ride captains. Ride captains were those riders stationed at

the head of the peloton who were charged with the responsibility

of maintaining the average speed for the ride. Often ride captains

rotated their duties, pulling at the head of the peloton for

a period of time until being relieved by other riders charged

with the ride captain role. On longer rides, ride captains received

their rest not by languishing at the rear of the peloton, but

by riding in a support vehicle.

Understanding that the success of Audax

brevet rides depended on the continued enthusiasm of younger

stronger riders, the Club Executive encouraged the participation

of these riders in cyclo-sportif events staged by cycle tourist

clubs. Audax ride captains had a record of outstanding success

at these events during the 1950's and 1960's. Among their competitors

in these events were riders from the Courbevoie-Asnieres and

the Levallois clubs, clubs that would eventually be employed

by the F.F.C.T. to reconstitute the A.C.P.

Among these cyclo-sportif events was the

Polymultipliee of Chanteloup, the hill climb event that had been

among the causes of the rupture of Audax cycling in the years

following the First World War. Other polymultipliee events were

held in Lyons, Clermont-Ferrand, and Dijon. Additional events

in the annual calendar were the 100 kilometers of the Union Sportive

du Metro, Les Boucles de la Seine, the Douze Heures de l'A.S.P.P.,

and the Vignt-Quatre Heures de Paris. The Fleche Veloccio event

organised by the A.C.P. at Easter, was considered to be part

of this cyclo-sportif programme. In 1961, a team of four Audax

ride captains rode 714 kilometers within the 24 hour time limit,

establishing a new distance record. They were to better this

mark by 24 kilometers in 1964. This calendar of cyclo-sportif

events contested by non-race licensed bicycle tourists was curtailed

in 1972 as a result of an agreement between the principal associations

of French cycling, the F.F.C. and the F.F.C.T.

A further initiative to promote the participation

of club members in club events was the creation of the Aigle

d'Or award. This award, initiated in 1950, was to be reserved

for those who had merited recognition through their participation

in Audax cycling brevets rather than the full gamut of Audax

brevets across the (then) four recognized Audax sport disciplines.

The Aigle d'Or was designed to be awarded to those club members

who had completed the full range of Audax brevets between 200

kilometers and 1000 kilometers, Paris-Brest-Paris, and a second

long distance event of 1000 kilometers or more.

Among the first recipients of the award

was Roger Outrequin, by that time President of the Club, and

with whom many of these new club initiatives was associated.

3. A Programme of Raids 1950 - 1960

It was Outrequin who was responsible for

the re-introduction of the Raid event to Audax cycling. The raid

had been a prominent part of the cycling programme of the Audax

Italiano cyclists, who made frequent long distance rides between

cities. There had been some inter-urban cycling events in the

early days of Audax cycling in France as well, but this tradition

had died out in the aftermath of the 1921 breakup.

Outrequin organized the first of the post-war

raids in 1950. This was a 1000 kilometer ride spread over three

days during which the newly instituted average ride speed of

22.5 k.p.h. was maintained. The ride connected Paris with the

Col Des Grands-Bois (now known as the Col De La Republique),

just south of the city of Saint Etienne. The Col is the site

of a monument to Paul De Vivie, the doyenne of French bicycle

tourism. Thirty-one cyclists undertook the ride of which twenty-nine

completed the event successfully. The four ride captains found

periodic relief by riding in the cab of a supporting van.

The success of this event prompted renewed

demand for further events of this kind. Following a hiatus in

1951, a Paris-Brest-Paris year, a raid of 1000 kilometers between

Paris and Nice was scheduled for 1952. This event was attended

by 118 riders of whom 104 finished. The route again ascended

the Col des Grands-Bois where a moment of respect was spent at

the site of De Vivie's monument. At Nice, some of the riders

joined with other cyclists from across France to participate

in the Semaine Federale, an annual event of the F.F.C.T., with

which the Audax raid had been timed to coincide. Again, as in

all of the raid events, the Audax formula of riding at a fixed

moderate speed under the control of a ride captain was observed.

At the end of 1953, Outrequin was ousted

from the club presidency. He left in his wake, however, a framework

for a continuing series of raid events. For 1954, he had laid

the foundations for a ride, together with the A.C.P. to celebrate

the fiftieth anniversary of the first Audax brevet. The ride

was to be a 600 kilometer brevet from Paris to Grenoble, with

an ascent on the following day of the Le Galibier to an assembly

at the foot of the monument erected in the mountain pass to the

memory of Henri Desgrange. Paris-Le Galibier has become an event

celebrated in the Audax calendar every ten years.

He laid the foundations, as well, for a

second Paris-Nice event in 1955. Paris-Nice Audax was to become

a regular part of the riding calendar, an eighth edition was

held in the year 2000 (the last reported in M. Deon's book, the

chronology of which ends in 2004). In addition, before his departure,

Outrequin had sketched the outlines of a raid to be held in 1960

between Paris and Rome which was to be the site of the Olympic

Games in that year. Following the success of the 1960 ride, Audax

riders conducted raids to Munich, site of the 1972 Olympic Games,

to Barcelona's Olympic Games in 1992, and to Athens, home to

the Olympic Games in 2004.

Through time, other long ride events have

been added to the Audax calendar. Bordeaux-Paris was the first

inter-urban road event of the safety bicycle era, and has retained

an importance in the minds of French cyclists for a long time.

Desgrange had refused to permit Audax cyclists to participate

in an event to be parallel to the professional race in the fifties,

a refusal that had prompted Raphael Boutin to create the 600

kilometer brevet event to be held in its stead. The ambition

to hold an Audax event in conjunction with the running of the

professional race was finally realised in 1977. The Audax event

was carried over the 600 kilometer route was carried on even

after the demise of the professional race, with editions occurring

every two to three years to the present day.

In addition to the Paris-Col des Grands-Bois

raid which has been run periodically since the first 1950 edition,

another commemorative ride has been staged several times between

Paris and La Rochelle, the birthplace of the founder of the U.A.C.P.,

Raphael Boutin. More recently, a 1000 kilometer ride has been

organized from Paris to Avignon and Valence. The final day of

this event features an ascent of Mont Ventoux where, in 1983,

a club member lost his life while attempting an early season

solo ascent of the climb. Pierre Kraemer had been a long time

member of the club, a ride captain, a sometime member of the

Executive, and a Super Audax Complet. His body was found in the

snow not far from where he had abandoned his bicycle. A small

memorial has been erected near the spot.

4. Audax Under One Roof: The Birth of the

Union Des Audax Francais

From the outset of the Audax movement,

there had been successive unsuccessful attempts to bring together

the scheduling and approval of the results of Audax brevet events

in the various sports disciplines in one umbrella organisation.

It had been the aim of Henri Desgrange to promote the development

of amateur athletes who were adept across a number of sports

activities. Early attempts to achieve this by grouping Audax

events in one club failed, as did Boutin's attempt to do something

similar in the 1920's. Conditions to achieve this aim proved

to be more propitious in the 1950's.

The hiking programme that had rallied club

members during the War years was continued in the post-War period.

Some club members remained enthusiastic about walking events

even after the of the full cycling calendar, with the result

that the club organised a first 100 kilometer hiking brevet in

1952.

Among those participating in this event

was Maurice Azalet. Azalet turned his attention to the non-cycling

Audax events with the consequence that, in 1954, he became the

second ever Super Audax Complet, the first to achieve this distinction

since the first award of this distinction in the early 1930's.

What the award entailed was the completion of the full gamut

of brevet events in each of the four sports disciplines that,

at that point, were sports in which Audax brevets were organized.

In other words, this meant the completion of 200, 300, 400, 600,

1000, and 1200 kilometer brevets in cycling, 100, 130, and 150

kilometer brevets in walking, a 6 kilometer swim brevet, and

a rowing brevet of 80 kilometers.

In the following year, 1955, Azalet was

elected to the club Executive and given responsibility for scheduling

and organizing walking events. Azalet fulfilled this mandate,

but took it a step beyond. He contacted the person then responsible

for the overall organization of Audax walking brevets in France,

and brought that person into the club. In effect, with this accession

the U.A.C.P. gained the organizational and approval rights for

all walking brevets scheduled in France.

Azalet went further and, again in 1955,

contacted the Societe Nautique de Lagny and the delightfully

named Les Pingouins de la Marne, the bodies charged with organizing

Audax brevets in rowing and swimming respectively. Both clubs

had experienced difficulties in re-launching a brevet programme

in the post-war period. Both proved amenable to handing off their

responsibilities to the U.A.C.P.

Assuming these new responsibilities, the

Union des Audax Cyclistes Parisiens contemplated a change in

name and mandate. These changes were ratified at the club's annual

members' meeting in 1955 to come into effect on January 1, 1956.

The successor organization was named the Union Des Audax Francais.

VI. The Rise and Decline Of Euraudax

1961 - 1985

1. Beginnings of Foreign Interest

The 1951 edition of Paris-Brest-Paris attracted

the attention of cyclists in other European nations, who sought

to emulate the experience of their French cousins. Rides organized

along Audax lines were organized in Belgium in the early 1950's.

These culminated in a 600 kilometer event in 1955 - Brussels-Paris-Brussels.

The Paris-Brest-Paris of the following year saw the first foreign

participation in the Audax event in the form of four Belgian

cyclists. Interest in Audax cycling continued to grow in Belgium

with the result that there were 24 Belgians among the 127 participants

in the Paris-Rome raid event of 1960.

Paris-Brussels-Paris 1961

In early 1961, an accord was reached with

the Royale Ligue Velocipedique Belge (R.L.V.B.) the organisation

that had, by that point, been organizing Audax-style events in

Belgium for a number of years. This accord established a full

brevet series in Belgium, including the 600 kilometer Brussels-Paris-Brussels

organized by the R.L.V.B. but homologated by the French club.

In that year, 269 brevets were submitted to the U.A.F. for homologation.

In the Paris-Brest-Paris Audax of that year,  35 of the 162 starters

were either Belgian or Dutch. The first Belgian 1000 kilometer

brevet - a virtual Tour Of Belgium - was staged in the following

year. Subsequent to their participation in that event, 10 Belgians

received the Aigle d'Or designation. 35 of the 162 starters

were either Belgian or Dutch. The first Belgian 1000 kilometer

brevet - a virtual Tour Of Belgium - was staged in the following

year. Subsequent to their participation in that event, 10 Belgians

received the Aigle d'Or designation.

2. The Creation Of Euraudax

From this point forward, Belgian participation

rates began to soar. In 1964, 1374 brevets ridden in Belgium

were homologated. By 1970 more Belgian brevet results were being

homologated than results for the entirety of France - 2221 in

Belgium as opposed to 717 in France. These participation rates

began to be mirrored, to a lesser extent, in the Netherlands

where the first 1000 kilometer brevet was ridden in 1970. This

event attracted 70 starters of whom 14 were French, 11 Belgian,

and 5 residents of Luxembourg.

The year 1970 saw the conclusion of an

agreement between the U.A.F. and the Belgian and the Dutch cycling

federations, the R.L.V.B. and the N.R.T.U. respectively. The

resulting concord, known as the "Charte de L'Euraudax"

came into effect at the beginning of 1971. The accord permitted

each national organization to schedule and homologate events

up to 600 kilometers in distance. The U.A.F. maintained certain

matters under its control, notably the award of the Aigle d'Or

designation and the distribution of control cards.

PBP Audax 1971

The accord allowed for the entry of other

nations following a two year probation period. Luxembourg was

accepted as a member later in 1971. German cyclists applied for

admission to Euraudax in 1972, and in 1975 the first Audax brevets

since the demise of Audax Italiano in the  conflagration of the

First World War, were held in Italy. Switzerland sought admission

in 1977 bringing membership in Euraudax to a total of seven nations. conflagration of the

First World War, were held in Italy. Switzerland sought admission

in 1977 bringing membership in Euraudax to a total of seven nations.

3. Decline

The year 1979 marked what was perhaps the

high water mark of Euraudax. In that year, a total of close to

18,200 brevets were reported as homologated across the seven

nation membership. Of these, something over one-third (7906 brevets)

were homologated in France. with the remainder homologated in

the five nations that reported their results.

By this time, however, the first signs

of the decline in European participation began to be observed.

Germany did not report results in 1979 nor, despite periodic

attempts by the French club to stimulate German interest, did

German results reach the levels attained in the first blush of

enthusiasm for Audax cycling. By 1982, neither Switzerland nor

Italy reported results. Homologation of brevets in the remaining

nations began a long slow decline until, by 1995, brevet homologation

was being reported in France and Belgium only. In Belgium, the

full series of brevet events was no longer being offered.

The intervening years have seen periodic

flurries of interest from cyclists in other nations - Portugal,

Sweden, and the United States. This, however, has never amounted

to more than a temporary enthusiasm.

It is hard not to associate the decline

in the fortunes of Euraudax with the creation of the international

institutions of randonneur cycling. The randonneur equivalent

of Euraudax was created some five years after the inception of

the Audax organisation, with Randonneurs Mondiaux succeeding

that organization in 1983, some seven years later. Audax cycling,

however, was unable to accrue to itself the advantages inherent

in being first in the field. Cyclists outside of France clearly

chose to pursue a cycling activity that was closer to cyclo-sportif

riding than to the disciplined group riding favoured by those

who participated in Audax events.

VII. Years Of Leveling Off 1985 - 2004

By the mid-1980's, it was beginning to

become apparent to many in the club that interest in Audax cycling

was beginning to level off. Not simply were the numbers of Audax

brevets organized and homologated falling off, but the average

age of those participating in Audax events was beginning to increase

significantly. Younger cyclists were looking elsewhere to fill

their recreational cycling pursuits.

A number of experiments were undertaken

to counteract these trends. Split brevets were tried - group

cycling outbound and free, or allure libre, cycling on the way

back. This experiment proved satisfying to very few. Similarly,

a few experimental rides  were conducted at a higher average speed

in the hope that a faster speed might attract younger riders.

These trials resulted in chaos on the roads with pelotons fracturing

into many parts. The average speeds established in the early

1950's were quickly re-established. were conducted at a higher average speed

in the hope that a faster speed might attract younger riders.

These trials resulted in chaos on the roads with pelotons fracturing

into many parts. The average speeds established in the early

1950's were quickly re-established.

More successful in stemming the tide of

rider defections were measures taken to reduce the amount of

night cycling involved in riding Audax brevets. Time limits of

the longer brevets were adjusted to permit longer stops at night,

permitting those planning brevet events to minimise or even eliminate

the amount of cycling after dark required to complete a brevet.

A further successful innovation has been

the introduction of the 100 kilometer brevet. When it was first

introduced, though conducted in the Audax manner, the 100 kilometer

ride was informal, that is to say, not homologated. Such had

proven to be the event's popularity, however, that by 1991, the

100 kilometer ride was made into a homologated brevet. It is

considered to be an introduction to Audax cycling and, as such,

is not counted towards any award or qualification. At a time,

however, when participation in other Audax events has declined,

interest in the 100 kilometer event remains strong and gives

a useful bump to the number of Audax events homologated each

year.

VIII. Conclusion

In 2003, members of the Union Des Audax

Francais organized and rode an eleven stage Tour de France. This

event, staged in the centenary year of the inaugural Tour de

France, was held to honour the club's connection with Henri Desgrange,

founder both of the Tour and of Audax cycling in France.

In so doing, the club celebrated its own

heritage and accomplishments over, what is now, more than a century

of organized activities. The club has remained faithful to Desgrange's

original vision of Audax sports events. It promotes physical

health and well being by providing demanding physical challenges

of a non-competitive nature. Though cycling remains the principal

focus of the club's programme, the club has acted to ensure that

Desgrange's original intention that participants in Audax events

be fit and competent across a number of sports disciplines is

encompassed in the club's events calendar.

The club has become both a celebrant and

a repository of cycling tradition. The club's staging of a Paris-Brest-Paris

Audax every five years carries on a cycling event that originates

at the dawn of the modern cycling era. The club's intermittent

participation in the Bordeaux - Paris event does the same thing.

Similarly, events commemorating the memory of great figures of

French cycling - notably Henri Desgrange and Paul De Vivie -

ensure that an important part of the heritage of French cycling

is not lost.

For the club's own members, however, its

principal achievement might lie elsewhere. As Monsieur Deon is

at pains to point out several times in his work, for many members,

the club has been a kind of second family. A social institution

that has provided diversion and comfort for its members and has

endured for over one hundred years, has every right to take pride

in its accomplishments.

October 2009

Photos added September 2012 |