|

Clifford Graves wrote prolifically on many of aspects of cycling. In this article he turns his attention to Paul de Vivie, aka "Velocio", the spiritual father of cyclo-tourisme and randonneur cycling. I copied this from the 1972 paperback edition of the 1970 publication "The Best of Bicycling". [Eric Fergusson - June 2005]  Paul de Vivie - Velocio ! 1853-1930 VELOCIO, GRAND

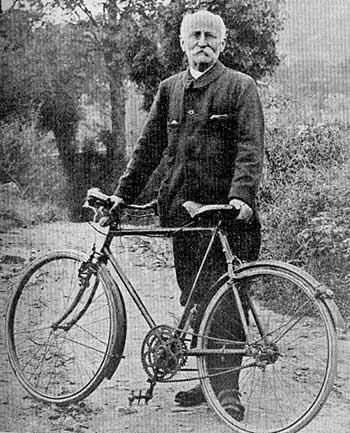

SEIGNEUR When a throng of cyclists from all corners of France converged on Saint-Etienne one day last July as they had done for more than forty years, they were paying homage to a man who accomplished great things in a small corner of the world. He was a man who devoted a lifetime to the perfection of the bicycle and the art of riding it, a man who inspired countless others through the strength of his character and the beauty of his writings, a man who even in his old age was capable of prodigious riding feats; in short, a man who might well be called the patron saint of cyclists. That man was Paul de Vivie, better know as Velocio. Paul de Vivie was born in 1853 in the small village of Perne in Southern France. His early years were unremarkable except that he distinguished himself by his love for the classics. If it is the mark of the educated man that he enjoys the exercise of his mind, Paul was exceedingly well educated. He graduated from the lycée, served an apprenticeship in the silk industry, and started his own business before he was thirty. With a beautiful wife and three handsome children, he seemed headed for a life of ease and elegance. The change came gradually. In 1881, when he was twenty-eight, he bought his first bicycle. It was an "ordinary" or high wheel, the safety bicycle still being in the future. The ordinary was a monster. With a precarious balance and an immoderate weight, it was a vehicle only for the strong and intrepid. That was exactly Paul's cup of tea. He began exploring the neighborhood on his newfangled contraption and he taught himself all the tricks of his wobbly perch. One day, on a bet, he rode sixty-six miles in six hours. This trip took him to the mountain resort of Chaise-Dieu. Suddenly he discovered a new world. The vigorous exercise, the fresh air, the beautiful countryside, these things took possession of him. He did not realize it but his life was beginning to take shape. The decade of the 1880s was a momentous one, both for Paul and for the bicycle. For Paul, it was the start of an arduous and lifelong pursuit. For the bicycle, it was the end of a long and painful gestation. This gestation had started in 1816 when the Baron von Drais in Germany discovered that he could balance two wheels in tandem as long as he kept moving. He moved by kicking the ground with his feet, and his vehicle came to be known as the draisine, or hobbyhorse. In 1829 Kirkpatrick Macmillan in Scotland eliminated the necessity for kicking by fitting cranks and treadles to the wheels. In 1863 or 1864 Pierre Michaux in Paris, with the help of his mechanic, Pierre Lallement, improved on the treadles by fitting pedals. This vehicle was a boneshaker, or velocipede. Neither the hobbyhorse nor the boneshaker was a hit because of the bruising weight and the merciless bouncing. In 1870 came the high wheel, and this did make a hit. Although the height of the wheel was a distinct and ceaseless hazard, this very height made it possible to travel farther with each revolution of the pedals. The high wheel caught the public fancy when four riders in 1872 rode the 860 miles in Great Britain from Lands End to John o'Groats in fifteen days. Clubs were formed, inns were opened, and touring started in earnest. The high wheel lasted until 1885 when it was replaced by the safety bicycle, which caused a further surge of excitement. Thus, when Paul de Vivie appeared on the scene in 1881, the bicycle was indeed on the threshold of its golden age. Paul rode his ordinary only a year. Then he bought a Bayliss tricycle, followed by a tandem tricycle and various other early models. These were the days when the bicycle industry was well established in Coventry, while France was lagging. Fired by enthusiasm, Paul started shuttling back and forth. He was searching for a better bicycle, a search that was taking more and more of his time. Clearly, he could not push this search and also run his silk business. He made his decision in 1887 at the age of thirty-four. In that year, he sold his silk business, moved to Saint-Etienne, opened a small shop, and started a magazine, Le Cycliste. Considering that he was invading a completely new field in which he had never had any training, it was a leap in the dark. In this leap, he discovered himself, and one of the things he discovered was that he could write. Words welled up within him as naturally as water tumbles down a cataract--and as gracefully. In his writing he always signed himself Velocio, and that became his name henceforth. It fitted him to perfection. For the first two years, Velocio was content to import bicycles from Coventry. But all the time he was experimenting. For us, who have grown up with the bicycle, the design problems that assailed Velocio seem elementary. To him, they were formidable. The safety bicycle of 1885 left many questions unanswered. The shape of the frame, the kind of transmission, the length of the cranks, the position of the handlebars, the type of tires, and above all the gearing, these were matters that caused endless discussion and experimentation, not only in the shop but on the road. Velocio's first model in 1889 was La Gauloise. It had the familiar diamond frame, a chain transmission, and a single gear of about fifty inches. It was the first bicycle produced in France, but it did not satisfy Velocio. The region around Saint-Etienne is mountainous. Velocio could see the need for variable gears. How to achieve these? In England, all the work was in the direction of epicyclic and planetary gears. Velocio struck out in a totally different direction. He conceived the idea of the derailleur. His first attempt was two concentric chain wheels with a single chain that had to be lifted by hand from one to the other. Now he had two gears. Next, he built two concentric chain wheels on the left side of the bottom bracket. Now he had four gears. In 1901 he came on the four-speed protean gear of the English Whippet. Here, the changes were made by the expansion of a split chain wheel. Partial reverse rotation of the pedals caused cams to open the two halves of the chain wheel and secure them in any one of the four positions by pawls. Velocio took this idea and worked it into his Chemineau, the derailleur as we now know it. This was in 1906. By 1908 four French manufacturers were introducing their own models because Velocio had been too busy to take out a patent. Incredible as it seems today, Velocio actually had to fight for the adoption of his derailleur gear. The cyclists of the period resented this marvelous invention as a stigma of weakness. They stoutly maintained that only a fixed gear could lead to smooth pedaling. Even Henri Desgrange, the originator of the Tour de France, attacked Velocio. To defend himself, Velocio wrote dozens of articles, answered hundreds of letters, cycled thousands of miles (average, 12,000 a year). At his suggestion the Touring Club de France organized a test in 1902. Competitors were to ride a mountainous course of 150 miles with a total climb of 12,000 feet. The champion of the day, Edouard Fischer, on a single-speed was pitched against Marthe Hesse on a Gauloise with a three-speed derailleur. The Gauloise won hands down. The newspapers were ecstatic because "the winner never set foot to the ground over the entire course." Still, Desgrange would not concede. Wrote he in his influential magazine, L'Equipe: "I applaud this test, but I still feel that variable gears are only for people over forty-five. Isn't it better to triumph by the strength of your muscles than by the artifice of a derailleur? We are getting soft. Come on, fellows. Let's say that the test was a fine demonstration--for our grandparents! As for me, give me a fixed gear!" Said Velocio with admirable restraint: "No comment." The battle of the derailleur dragged on for a full thirty years. It was not until the 1920s that it was finally won. Velocio himself advocated wide-ratio gears for touring: from 35 to 85. His normal riding gear was 72. In this battle for the derailleur gear, Velocio had a powerful weapon in his magazine, Le Cycliste. By 1900 this publication had grown from a fragile and unpretentious sheet of local circulation to an eloquent and influential journal that was widely read because of its incisive articles and vivid writing. Much of this writing was by Velocio himself, who never tired of describing his fantastic tours in the most colorful language. To read Le Cycliste is to read the history of cycle touring. But Le Cycliste is more than a repository of history. With a passage of the years, Velocio became a philosopher. Having given up the quest for money and fame in the dim days of 1887, he could look at the world with complete equanimity. He read the classics in the original, and he applied their teachings to his own life. Between his articles on cycling, he counseled his readers on diet, on exercise, on hygiene, on physical fitness, on self-discipline, in fact on all the facets of what is commonly called a well-rounded life. His theme was a sound mind in a sound body. In wine-drinking France he spoke out unequivocally for sobriety; and he warned against the hazards of smoking sixty year before a presidential commission in the United States did so. These statements he made only after he had proved the benefits on himself because he was not a man to mouth platitudes. Thus, Le Cycliste became much more than a magazine for cyclists. It became a manifesto of brisk living, the credo of a dedicated man, a profession of faith. Brisk and dedicated are also the words to describe Velocio as a cyclist. By nature, temperament, and physique he was what he called a "veloceman." Something of his enthusiasm can be gleaned from his ride to Chaise-Dieu in 1881, sixty-six miles in six hours on a clumsy high wheel. His serious cycling started in 1886 on a Eureka with solid rubber tires (pneumatics came in 1889). On this bicycle he rode 90 miles from Saint-Etienne to Vichy before noon. In 1889 he made his first 150-miler, a round trip from Saint-Etienne to Charlieu on a British Star weighing fifty-five pounds. But these were only the probings of the beginner. Partly from his tremendous drive and partly from his compelling desire to show what the bicycle was capable of, he began to extend his tours. Sometimes alone, sometimes with a small group of friends, he would ride through the night, through the second day, through the second night, and into the third day without more that an occasional rest to eat or change clothes. Consider these feats: In 1900, when he was forty-seven, he toured the high passes in Switzerland and Italy, 400 miles with a total climb of 18,000 feet, in forty-eight hours. For Easter in 1903, at the age of fifty, he rode from Saint-Etienne to Menton and back in four days: 600 miles on a bicycle weighing sixty-six pounds including baggage. For Christmas 1904 he cycled from Saint-Etienne to Arles and back on a night so cold that icicles formed on his moustache. His "spring cure" in 1910 took him from Saint-Etienne to Nice, a distance of 350 miles, in thirty-two hours. At Nice he joined a group of friends for 250 miles of leisurely touring in three days. The following summer he tackled one of the highest Alpine passes, the Lautaret, in the company of a young friend: 300 miles in thirty-one hours. In 1912 also, when he was fifty-nine, he undertook an experimental ride from Saint-Etienne to Aix-en-Provence. 400 miles in forty-six hours, at the end of which he had to admit that his companion, thirty-five, tolerated the second night on the road better than he. "From now on," he wrote in Le Cycliste, "I will limit myself to stages of forty hours and leave it to the younger generation to prove that the human motor can run for three days and two nights without excessive fatigue." "Every cyclist between twenty and sixty in good health," wrote Velocio with the fervor of a missionary "can ride 130 miles in a day with 600 feet of climbing, provided he eats properly and provided he has the proper bicycle." Proper food, in his opinion, meant no meat. A proper bicycle meant a comfortable bicycle with wide-ratio gears, a fairly long wheelbase, and wide-section tires. A bicycle with close-ratio gears, a short wheelbase, and narrow-section tires will roll better at first, he pointed out, but it will wear its rider down on long-distance attempts. The first consideration is comfort. His diet on tour consisted of fruit, rice, cakes, eggs, and milk. Obviously, Velocio was a very special kind of cycle tourist. Not for him the Sunday ride with stops every half hour. "Cycling in this fashion is undoubtedly enjoyable," he wrote, "but it ruins your rhythm and squanders your energy. To get in your stride, you have to use a certain amount of discipline. My aim is to show that long rides of hundreds of miles with only an occasional stop are no strain on the healthy organism. To prove this point is not only a pleasure, it is a duty for me." Velocio was sometimes criticized for his long-distance riding. It was said that he was hypnotized by speed and mileage and that he could not see anything of the country at that rate. He answered: "These people do not realize that vigorous riding impels the senses. Perception is sharpened, impressions are heightened, blood circulates faster, and the brain functions better. I can still vividly remember the smallest details of tours of many years ago. Hypnotized? It is the traveler in a train of car who is hypnotized." If anyone doubts that Velocio could see anything, let him read short passage from a story of an Alpine crossing: "A shaft of gold pierced the sky and came to rest on a snowy peak, which, moments before, had been caressed by soft moonlight. For an instant, showers of sparks bounced off the pinnacle and tumbled down the mountain in a heavenly cataract. The king of the universe, the magnificent dispenser of light and warmth and life, gave notice of his imminent arrival. But only for an instant. Like a spent meteor, the spectacle dissolved in the sea of darkness that engulfed me in the depths of the gorge. The scintillating reflections, the exploding fireballs--they were gone. Once again, the snow assumed its cold and ghostly face." Could this passage have come from the pen of a cyclist obsessed by the mechanics of cycling? No--Velocio loved his bicycle because it brought him priceless freedom, because it gave him exhilarating exercise, because it opened his mind to the music of the wind, because it imparted a delicious feeling of being alive. "After a long day on my bicycle," he said, "I feel refreshed, cleansed, purified. I feel that I have established contact with my environment and that I am at peace. On days like that I am permeated with a profound gratitude for my bicycle." It was Velocio who coined the term "little queen" for the bicycle, a term that is still in common use in France. And again: "Even if I did not enjoy riding, I would still do it for my peace of mind. What a wonderful tonic to be exposed to bright sunshine, drenching rain, choking dust, dripping fog, frigid air, punishing winds! I will never forget the day I climbed Puy Mary [a 5,000-foot eminence near his home]. There were two of us on a fine day in May. We started in the sunshine and stripped to the waist. Halfway, clouds enveloped us and the temperature tumbled. Gradually it got colder and wetter, but we did not notice it. In fact, it heightened our pleasure. We did not bother to put on our jackets or our capes, and we arrived at the little hotel at the top with rivulets of rain and sweat running down our sides. I tingled from top to bottom." Passages almost exactly like this can be found in the books of John Muir. It was from experiences like these that

Velocio formulated the seven commandments for the cyclist: Velocio was not a promoter. His efforts to create a national bicycle touring society like the Cycle Touring Club in England floundered, and he never had an organized bicycle club even in his hometown. What he did have was a constantly growing body of friends and admirers who gathered around the master in his shop, at the rallies, and on his tours. Those who lived nearby formed a loose-knit group known as L'Ecole Stéphanoise, or School of Saint-Etienne. A quorum was always on hand for Velocio's favorite ride to the top of the Col du Grand Bois. It was this ride that eventually grew into Velocio Day. The Col du Grand Bois is a 3,800-foot passage across the Massif du Pilat. The road starts on the outskirts of Saint-Etienne and rises without letup over a distance of eight miles. Velocio used to make this ride as a constitutional before breakfast. In 1922 his friends surprised him by inviting all cyclists in the area to join in the ride in a gesture of reverence. Today, Velocio Day is a unique spectacle, the only one of its kind in the world. This gradual emergence of Velocio as a dominant figure, not only among cyclists but among the people of his age, is one of the most interesting things about the man because he never made a conscious attempt to attract public notice. All he wanted was his bicycle and his friends. He never moved his shop, he never had much money, and he never rested on his laurels. Twice a year, he would have a little notice in Le Cycliste, inviting all and sundry to a rally. These rallies became famous. At first strictly local affairs, they eventually became national institutions and some of them are still observed, such as the Easter gathering in Provence. Velocio himself was not aware of his stature until he was invited to appear in Paris in the Criterium des Vieilles Gloires when he was seventy-six. Then it was obvious that he completely over-shadowed all the others. Thousands gathered around him, just to shake his hand and wish him well. On February 27, 1930, Velocio started his day with a reading from one of the classics, as was his custom. It was a letter from Seneca to Lucilius. "Death follows me and life escapes me. When I go to sleep, I think that I may never awake. When I wake up, I think that I may never go to sleep. When I go out, I think that I may never come back. When I come back, I think that I may never go out again. Always, the interval between life and death is short." Velocio went out. Traffic was heavy, and he decided to walk and lead his bicycle. He crossed the street ahead of the streetcar coming from his left, saw another car coming from his right, stepped back, and was hit by the first. It was a mortal blow. He died clutching his beloved bicycle. Today, thirty-five years later, Velocio lives on, while others, equally dedicated and equally inventive, are forgotten. Why is this? It is because Velocio used his bicycle to demonstrate the great truths. Velocio's influence grew, not because of his exploits on the bicycle, but because he showed how these exploits will shape the character of a man. Velocio was a humanist. His philosophy came from the ancients who considered discipline the cardinal virtue. Discipline is of two kinds: physical and moral. Velocio used the physical discipline of the bicycle to lead him to moral discipline. Through the bicycle he was able to commune with the sun, the rain, the wind. For him, the bicycle was the expression of a personal philosophy. For him, the bicycle was the road to freedom, physical and spiritual. He gave up much, but he found more. Velocio--the cyclists of the world salute you. After typing out this article and preparing this page I discovered that someone else had beat me to it... This article can also be found on Adrian Hand's cycling pages -> Velocio. A new book on Velocio is scheduled for release in 2005 -> "Velocio: l'évolution du cycle et le cyclotourisme" by Raymond Henry. [EF]. June 2005 |